But Malmo FF was not capable of a double – they did not reach even the Cup final. It could be that Swedish football had weak year, judging by combined information: easy, too easy, victory of Malmo FF; the whole lot of better known clubs slipping down the table, presenting no challenge whatsoever; lean best goalscorers, with only 15 goals each, and not exactly great players – Reine Almqvist (IFK Goteborg) and Mats Aronsson (Landskrona BoiS). Since the predicament of Swedish football was to be measured by international success, the top scorers were actually sign of decline – they did not wet foreign appetites. Aronsson never played for a foreign club and Almqvist only 'kind of' - he joined NASL in her decline: in 1980-81 he played 5 regular matches for Seattle Sounders, adding 17 more in indoor soccer. And, finally, the Swedish Cup final opposed more or less unlikely clubs – Hammarby IF and Osters IF.

Standing, from left: Mats Werner, Börje Forsberg, Jan Sjöström, Jan Svensson, Michael Andersson.

Crouching: Kenneth Ohlsson, Billy Ohlsson, Gunnar Wilhelmsson, Johan Hult, Bo Mattsson, Thom Åhlund.

Hardly a strong squad, but more importantly Hammarby IF had so-so season, finishing 7th in the League. Their best years seemed hopelessly in the past. Naturally, reaching the Cup final was great for them, but it was also the end of their hopes, for they lost 0-1.

The winners were excited:

Osters IF knew success in the past, wining the championship, but never the Cup. They had even weaker league season than Hammarby IF , finishing 9th. Their history was poorer than Hammarby's and the present time – may be bleaker, for they had, theoretically, fewer resources than the clubs from Stockholm, Goteborg, and Malmo. Vaxjo, their hometown, is hardly even known outside Sweden – a typical small provincial town and the fate of clubs from such towns is painfully familiar... May be just reaching the final was to be considered success, but the boys did not think so and they won the Cup. The first and... last Cup won by Osters IF. A rare victory, never to be repeated? Apparently, back in Vaxjo they did not think that either, but the future should stay unknown. And speaking of the future, Osters IF may win a second Cup one day...

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Monday, October 29, 2012

Swedish football was unique: it was at best semi-professional, so no club had big money and good players had no reason to move to better paying club. If they did, it was in entirely different direction – to foreign lands. In the same time living standard was high in the country, and a player did not see a reason to move out from his original club. Thus, clubs remained relatively equal, there was no dominant two-three clubs, collecting the best talent of the country and staying head and shoulders above the rest. Fair game, without permanent favourites – one year some clubs were up, down in the next, champions were hard to predict, let alone to expect same clubs staying constantly on top. And 1977 was no different – the better known clubs spread through the league, some near relegation zone, like AIK and Orebro SK, others at more comfortable positions. IFK Norrkoping ended 4th, the best among the usual bunch.

May be a bit disappointing for their fans, but otherwise typical season: among fairly equal clubs, Norrkoping managed to climb near the top, yet not at the very top. A typical squad too – to outsiders, largely unknown players. May two or three classier, may be some good enough to play somewhere in Europe, but no actual or potential great stars.

And because all clubs were like that, lesser known clubs had strong season this year:

IF Elfsborg finished second, a big success for them, for normally they were not even in First Division.

Just bellow them another relative 'unknown' enjoyed bronze medals: Kalmar FF.

Going to play in the UEFA Cup was high point for both Kalmar FF and IF Elfsborg, but it was clear that neither club was to last for long in the harsh European environment. And both clubs had to just cherish the moment, for who knows what may happen the next year? Relegation was quiet possible; staying on top – unlikely. The fate of small clubs, even in relatively equal league, is well known: they do not build dynasties... their best years are short-lasting, ephemeral.

Which leaves us to the champions, who were neither ephemeral, nor short-lasting: Malmo FF. Ah, expected... may be. Because of the Swedish conditions, I am reluctant to call Malmo FF 'dominant', although they were by far the best Swedish club in the 1970s. Practically since the beginning of the decade they maintained the same squad and the same coach. Very experienced by now, they were able to stay among the top 3-4 clubs every year, but this to a point was due to the general unpredictability of the other clubs. The club management was no doubt wise and perhaps money were better than elsewhere, for the players stayed loyally, yet, Malmo FF was a bit peculiar, for practically no players of this squad went abroad. Stability is good , but … if this was the best club, with obviously the best players, how come nobody wanted them for love or money? Most likely the secret was the collective strength of the team, not the particular abilities of individual players – after all, their English coach Houghton built a team true to his vision: both coach and players remained in seemingly relaxed atmosphere. Stability and experience permitted Malmo FF to stay on top and often to win titles. Because of that they got another advantage: regular participation in the European club tournaments, adding further experience and confidence. In Sweden Malmo FF were difficult to beat, their experience was enough to keep them among top 3-4 clubs in a weaker season.

But there was more: in most countries a team like Malmo's would be in obvious decline and in need of radical major rebuilding. A life-span of great squad is about 5 years, decay apparent in the 4th. Malmo FF differed – it was running strong already about 8 or nine years with the same team. Yes, players left for one or another reason; new ones came, but it was gradual change, nothing drastic. No stars were recruited either – it was a squad of , so to say, local boys, staying together for very long time. May be the lack of constantly strong rivals helped, may be the ups and downs of the rest of the league benefited Malmo, may be the atmosphere in the club built relaxed confidence, but the life-span of the squad was unusual. When the opposition had general weak season, Malmo FF won easily: in 1977 they finished with most wins, least losses, best scores, best defensive record, and devastating 8 points lead. Overwhelming champions – a team tired and depending only on experience is not capable of such winning even in a weak league.

Standing, from left: Bob Houghton (coach), Bo Larsson, Krister Kristensson, Jan Möller, Anders Ljungberg, Tommy Hansson,

Tommy Larsson, Egon Jönsson (manager).

Sitting: Roland Andersson, Magnus Andersson, Tommy Andersson, Claes Malmberg, Ingemar Erlandsson, Thomas Sjöberg,

Roy Andersson

Not tired yet from winning or business as usual? One more title for this squad. And they were not done yet – in fact, their finest season was still in the future.

May be a bit disappointing for their fans, but otherwise typical season: among fairly equal clubs, Norrkoping managed to climb near the top, yet not at the very top. A typical squad too – to outsiders, largely unknown players. May two or three classier, may be some good enough to play somewhere in Europe, but no actual or potential great stars.

And because all clubs were like that, lesser known clubs had strong season this year:

IF Elfsborg finished second, a big success for them, for normally they were not even in First Division.

Just bellow them another relative 'unknown' enjoyed bronze medals: Kalmar FF.

Going to play in the UEFA Cup was high point for both Kalmar FF and IF Elfsborg, but it was clear that neither club was to last for long in the harsh European environment. And both clubs had to just cherish the moment, for who knows what may happen the next year? Relegation was quiet possible; staying on top – unlikely. The fate of small clubs, even in relatively equal league, is well known: they do not build dynasties... their best years are short-lasting, ephemeral.

Which leaves us to the champions, who were neither ephemeral, nor short-lasting: Malmo FF. Ah, expected... may be. Because of the Swedish conditions, I am reluctant to call Malmo FF 'dominant', although they were by far the best Swedish club in the 1970s. Practically since the beginning of the decade they maintained the same squad and the same coach. Very experienced by now, they were able to stay among the top 3-4 clubs every year, but this to a point was due to the general unpredictability of the other clubs. The club management was no doubt wise and perhaps money were better than elsewhere, for the players stayed loyally, yet, Malmo FF was a bit peculiar, for practically no players of this squad went abroad. Stability is good , but … if this was the best club, with obviously the best players, how come nobody wanted them for love or money? Most likely the secret was the collective strength of the team, not the particular abilities of individual players – after all, their English coach Houghton built a team true to his vision: both coach and players remained in seemingly relaxed atmosphere. Stability and experience permitted Malmo FF to stay on top and often to win titles. Because of that they got another advantage: regular participation in the European club tournaments, adding further experience and confidence. In Sweden Malmo FF were difficult to beat, their experience was enough to keep them among top 3-4 clubs in a weaker season.

But there was more: in most countries a team like Malmo's would be in obvious decline and in need of radical major rebuilding. A life-span of great squad is about 5 years, decay apparent in the 4th. Malmo FF differed – it was running strong already about 8 or nine years with the same team. Yes, players left for one or another reason; new ones came, but it was gradual change, nothing drastic. No stars were recruited either – it was a squad of , so to say, local boys, staying together for very long time. May be the lack of constantly strong rivals helped, may be the ups and downs of the rest of the league benefited Malmo, may be the atmosphere in the club built relaxed confidence, but the life-span of the squad was unusual. When the opposition had general weak season, Malmo FF won easily: in 1977 they finished with most wins, least losses, best scores, best defensive record, and devastating 8 points lead. Overwhelming champions – a team tired and depending only on experience is not capable of such winning even in a weak league.

Standing, from left: Bob Houghton (coach), Bo Larsson, Krister Kristensson, Jan Möller, Anders Ljungberg, Tommy Hansson,

Tommy Larsson, Egon Jönsson (manager).

Sitting: Roland Andersson, Magnus Andersson, Tommy Andersson, Claes Malmberg, Ingemar Erlandsson, Thomas Sjöberg,

Roy Andersson

Not tired yet from winning or business as usual? One more title for this squad. And they were not done yet – in fact, their finest season was still in the future.

Saturday, October 27, 2012

Another enigmatic country – Sweden. Few, if any, news. Well respected national team, modest club football, better known to specialists than to the general public outside Sweden. Swedish players were known largely when they played abroad and seemingly the best were already there – in West Germany, Holland, Belgium, etc. 1977 was quiet year in a way – no exciting new name made headlines abroad. May be Swedish talent was coming to end? May be not, for Swedish clubs were always modest and the country's strength was based on the national team. Club football, at least to an outsider, was associated with Malmo FF. It was there great decade indeed. Which is not the whole Swedish football of course. The championship unfolded its own drama: down there was the struggle to remain in top flight. More or less, it was a battle for escaping second to last place – IFK Sundsvall lost it, finishing 13th and relegated.

Not much to say about IFK Sundsvall – modest club even by Swedish standards and quite expected candidates for relegation. They finished 8 points above the 14th club, but so what... not enough for survival.

Dead last and hopelessly so, for they managed to collect only 12 points, was a curious club: last place in First Division was their biggest success ever.

Standing from left: Coach "Söla", Tomas Månsson, Lasse Richt, Ruben Svensson, Ronny Larsson, Anders Wickman, Christer Johansson, lagl. KJ Månsson.

Bottom: "Gatta" Svensson, Peter Lindholm, Robban Jonsson, Pe-Ge Nordahl, Uffe Spångberg, Lasse Grönqvist ,"Lillen" Svensson

Unrecognizable, right? This is BK Derby from Linkoping. Old club, but normally playing down in the lower divisions. In 1976 they won promotion and joined First Division for 1977 season. BK Derby never played that high before, but they were no match for the rest of the league. They lost 17 out of total 26 championship matches. They scored the least goals in the league and their defense was also unmatched: it was the worst. Down they went, never to return again. To this day 1977 remains the only season BK Derby played in First Division, thus, 1977 is their best year ever... Funny thing, the football.

Not much to say about IFK Sundsvall – modest club even by Swedish standards and quite expected candidates for relegation. They finished 8 points above the 14th club, but so what... not enough for survival.

Dead last and hopelessly so, for they managed to collect only 12 points, was a curious club: last place in First Division was their biggest success ever.

Standing from left: Coach "Söla", Tomas Månsson, Lasse Richt, Ruben Svensson, Ronny Larsson, Anders Wickman, Christer Johansson, lagl. KJ Månsson.

Bottom: "Gatta" Svensson, Peter Lindholm, Robban Jonsson, Pe-Ge Nordahl, Uffe Spångberg, Lasse Grönqvist ,"Lillen" Svensson

Unrecognizable, right? This is BK Derby from Linkoping. Old club, but normally playing down in the lower divisions. In 1976 they won promotion and joined First Division for 1977 season. BK Derby never played that high before, but they were no match for the rest of the league. They lost 17 out of total 26 championship matches. They scored the least goals in the league and their defense was also unmatched: it was the worst. Down they went, never to return again. To this day 1977 remains the only season BK Derby played in First Division, thus, 1977 is their best year ever... Funny thing, the football.

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

The Cup final opposed Steaua and Universitatea, second and third in the championship, Bucharest vs Craiova. Trying to win at least something, the enemies fought and at the end the provincials prevailed 2-1. Steaua was left empty-handed this season. For Universitatea the Cup was a success.

Happy indeed: winning their very first cup! With that added to their first title, won in 1973-74, Universitatea firmly established itself among the best Romanian clubs. It was to stay on top permanently – more trophies were to come soon.

Yet, to a point, the winners in 1977 represented transitional time

: Dinamo and Universitatea depended on well established players, representing the 'lost' 1970s generation. Both clubs had to make changes, introduce new players, build well-rounded squads. So far, it looked like one-two outstanding players were enough for winning at home – but not abroad. Steaua looked more like team for the future – it was younger squad, not exactly at its prime yet, and therefore unable to maintain strong performance. But it was a squad coming inevitably to maturity, whereas Dinamo and Universitatea were to really start new teams.

Happy indeed: winning their very first cup! With that added to their first title, won in 1973-74, Universitatea firmly established itself among the best Romanian clubs. It was to stay on top permanently – more trophies were to come soon.

Yet, to a point, the winners in 1977 represented transitional time

: Dinamo and Universitatea depended on well established players, representing the 'lost' 1970s generation. Both clubs had to make changes, introduce new players, build well-rounded squads. So far, it looked like one-two outstanding players were enough for winning at home – but not abroad. Steaua looked more like team for the future – it was younger squad, not exactly at its prime yet, and therefore unable to maintain strong performance. But it was a squad coming inevitably to maturity, whereas Dinamo and Universitatea were to really start new teams.

Monday, October 22, 2012

Up the table were the usual small cubs struggling for survival and the solid unambitious mid-table clubs. UTA Arad were seemingly in decline (12th place this season), Arges (Pitesti) had weak year (11th), Politehnica (Timisoara) was climbing up (6th), Jiul (Petrosani) was perhaps a bit higher than normal (5th), but... all that was pretty much in the realm of mid-table: there was sharp 4-point divide between 3rdh and 4th place, and the group between 4th and 17th place was divided by 7 points – the champions were 12 points above ASA at 4th, and 19 points above Progresul, 17th.

Arges (Pitesti), having a weak season and finishing at unlikely low place. Even the shirt of the Italian national team their goalkeeper sported did not help.

ASA Targu Mures finished 4th thanks to better goal difference. Those were strong years for the club – they never won anything, so to grab a UEFA Cup spot amounts to success. ASA managed to stay on the top of the mid-table clubs for few years, but that was all.

ASA were club belonging to the Army and thanks to that they were perhaps able to take desirable players from most other clubs and build a strong squad. But to belong to the Army was also their doom, for inevitably they were subordinated to Steaua (Bucharest). Not only they were recruiting players only after Steaua satisfied its appetite, but 'big brother' took whoever they wanted from ASA as well. At the best, ASA was capable of keeping team good for 4th place and to stay happy with small results. Participation in the UEFA Cup was really the best they can do.

At the end, it was really a race of three clubs – Steaua, Dinamo, and Universitatea (Craiova). The 'students' were not even in the race – solid third, 4 points bellow the silver medalists. The Army were not real competitors either – they fought, won exactly the same number of matches the champions did – twenty in total – but lost way too many games and ended 'comfortably second. The Police ruled – Dinamo won their 9th championship.

Nothing new about the champions really – if not Steaua, Dinamo then... but in a way the squad exemplifies the 'in between' state of Romanian football: by now the stars of the 1960s were coaches – two of the legendary six Nunweiller brothers were at the Dinamo's helm. Cornel Dinu was nearing retirement, the link with the last international Romanian success. The other well known names were from the 'lost' generation of the 1970s: C. Stefan, A. Satmareanu, G. Sandu, M. Lucescu, D. Georgescu. Mircea Lucescu became famous coach indeed, but the player Lucescu did not get much fame... and even less Dudu Georgescu. Well, he was the best known Romanian player at the time thanks to his goals: this season he scored 47! Not only the Golden Shoe was his for second time after he won it in 1975, but the fantastic number of goals was all-time European record.

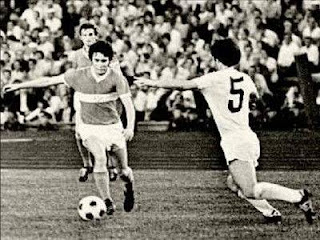

Another goal for Dudu – quite impressive too. It could be said that he was responsible for Dinamo's success, for the rest of the team was not exactly great as a whole. But one wonder was not enough for strong and successful national team... Georgescu was unlucky to play in the 1970s: if he was born a few years later, he would have much more talented teammates around. It is even a bit troublesome to judge his unusual goal-scoring ability: the 1970s are very distant now, and by the end of the 1980s the Romanian goal-fixing loomed and destroyed the original Golden Shoe competition. Georgescu was not tainted, but... who really knows? Manipulating scores was not at all difficult in a Communist state – I have seen it myself: opposition practically not playing, referees giving imaginary penalty, goalkeeper not even pretending to save his net, great goal-scorer at the end... and a Bronze Shoe comes along. Georgescu scored a lot in the domestic championship, but not that much in international matches. True, he had not so strong teammates and it was therefore much more difficult to score abroad, but the difference is nevertheless fruit for thought. Yet, he was good: he practically scored a goal in every second match he played for the Romanian national team. Unfortunately, he never played professionally abroad – not his fault, for he was of the generation not allowed to do that – and there is no way to evaluate him 'independently', so to say. Let not judge him harshly – Georgescu scored fantastic number of goals. In Romania, he was top scorer for a third time in a row. Too bad he had to play in the 1970s.

Arges (Pitesti), having a weak season and finishing at unlikely low place. Even the shirt of the Italian national team their goalkeeper sported did not help.

ASA Targu Mures finished 4th thanks to better goal difference. Those were strong years for the club – they never won anything, so to grab a UEFA Cup spot amounts to success. ASA managed to stay on the top of the mid-table clubs for few years, but that was all.

ASA were club belonging to the Army and thanks to that they were perhaps able to take desirable players from most other clubs and build a strong squad. But to belong to the Army was also their doom, for inevitably they were subordinated to Steaua (Bucharest). Not only they were recruiting players only after Steaua satisfied its appetite, but 'big brother' took whoever they wanted from ASA as well. At the best, ASA was capable of keeping team good for 4th place and to stay happy with small results. Participation in the UEFA Cup was really the best they can do.

At the end, it was really a race of three clubs – Steaua, Dinamo, and Universitatea (Craiova). The 'students' were not even in the race – solid third, 4 points bellow the silver medalists. The Army were not real competitors either – they fought, won exactly the same number of matches the champions did – twenty in total – but lost way too many games and ended 'comfortably second. The Police ruled – Dinamo won their 9th championship.

Nothing new about the champions really – if not Steaua, Dinamo then... but in a way the squad exemplifies the 'in between' state of Romanian football: by now the stars of the 1960s were coaches – two of the legendary six Nunweiller brothers were at the Dinamo's helm. Cornel Dinu was nearing retirement, the link with the last international Romanian success. The other well known names were from the 'lost' generation of the 1970s: C. Stefan, A. Satmareanu, G. Sandu, M. Lucescu, D. Georgescu. Mircea Lucescu became famous coach indeed, but the player Lucescu did not get much fame... and even less Dudu Georgescu. Well, he was the best known Romanian player at the time thanks to his goals: this season he scored 47! Not only the Golden Shoe was his for second time after he won it in 1975, but the fantastic number of goals was all-time European record.

Another goal for Dudu – quite impressive too. It could be said that he was responsible for Dinamo's success, for the rest of the team was not exactly great as a whole. But one wonder was not enough for strong and successful national team... Georgescu was unlucky to play in the 1970s: if he was born a few years later, he would have much more talented teammates around. It is even a bit troublesome to judge his unusual goal-scoring ability: the 1970s are very distant now, and by the end of the 1980s the Romanian goal-fixing loomed and destroyed the original Golden Shoe competition. Georgescu was not tainted, but... who really knows? Manipulating scores was not at all difficult in a Communist state – I have seen it myself: opposition practically not playing, referees giving imaginary penalty, goalkeeper not even pretending to save his net, great goal-scorer at the end... and a Bronze Shoe comes along. Georgescu scored a lot in the domestic championship, but not that much in international matches. True, he had not so strong teammates and it was therefore much more difficult to score abroad, but the difference is nevertheless fruit for thought. Yet, he was good: he practically scored a goal in every second match he played for the Romanian national team. Unfortunately, he never played professionally abroad – not his fault, for he was of the generation not allowed to do that – and there is no way to evaluate him 'independently', so to say. Let not judge him harshly – Georgescu scored fantastic number of goals. In Romania, he was top scorer for a third time in a row. Too bad he had to play in the 1970s.

Saturday, October 20, 2012

Enigmatic Romanians. Little was really known about them, no major news, but they were well respected. Seemingly, on old reputation alone, for they were failing to reach final stages of international tournaments steadily after their last appearance at the World Cup finals in 1970. The clubs fared no batter than the national team, normally eliminated in the early stages of the European club tournaments. Yet, Romanian teams were considered dangerous. Judging by results – kind of 'second best', difficult to beat, but beatable. The lack of ready information makes evaluation a guessing work: were they in crisis, or not? Did they adapt to the changes in football, or did they lagged behind? One thing was more or less certain: Romania was caught in the unavoidable struggle of changing generations. The generation of the late 1960s, who made the last appearance at the 1970 World Cup was retiring. There was no new great one yet, may be it was still too young to make impression. In the gap 'a between' generation carried on – second-string players, local heroes, never more than just local heroes, and the unlucky bright players, too few to really shine, doomed to be too young or too old, and therefore unlucky to participate in the better days of Romanian football. Domestic football chugged along, with its ups and downs, relatively competitive championship, but there was hardly anything great. The 1970s were the strong years of Universitatea (Craiova) and Arges (Piteisti), but there were always few strong provincial clubs in Romania, so tot speak of shift of power is ungrounded. The grands from Bucharest – Steaua and Dinamo – were perhaps not at their best, but still both maintained their positions and were capable of winning, no major slips. The rest of the league shuffled, but it was not unexpected in a relatively strong and equal league. No 'earthquakes'.

The three promotional spots were won by Olimpia Satu Mare, CS Targoviste, and Petrolul Ploeisti. Targoviste were relative newcomers; Olimpia more or less too. Not a single newcomer was expected to become suddenly a sensation.

Petrolul (Ploeisti), coming back to First Division. Coming back, but not to take the Romanian league by storm.

The newcomers were to replace the last three in the 1976-77 season, which were more interesting names: Rapid (Bucharest, 16th), Progresul (Bucharest, 17th), and FCM Galati (last 18th place). FCM Galati were obvious and hopeless outsiders, quickly returning to the Second Division. Rapid and Progresul were unlikely losers – both clubs knew success, both were in the shadow of Steaua and Dinamo, so never able to build and keep consistently strong squads, but their lowest point would have been in mid-table, not at the bottom. Unlike the pariahs, FCL Galati, these two fought and may be were a bit unlucky to end in the relegation zone, yet, there they were and Bucharest lost 2 out of 5 First league clubs. The sudden decrease may be described as a decline of Bucharest football, but I am reluctant, largely because, with the exception of Universitatea (Craiova), provincial Romania did not produce any long-lasting strong team. Bucharest was challenged, but not destroyed. There was only an ironic twist, if the names of the relegated are 'interpreted': Rapid was rapidly going down, and Progresul, roughly meaning 'progressive', were actually regressive. However, outside the misfortune of of the particular clubs, no major conclusion of the state of Romanian football could be made.

The three promotional spots were won by Olimpia Satu Mare, CS Targoviste, and Petrolul Ploeisti. Targoviste were relative newcomers; Olimpia more or less too. Not a single newcomer was expected to become suddenly a sensation.

Petrolul (Ploeisti), coming back to First Division. Coming back, but not to take the Romanian league by storm.

The newcomers were to replace the last three in the 1976-77 season, which were more interesting names: Rapid (Bucharest, 16th), Progresul (Bucharest, 17th), and FCM Galati (last 18th place). FCM Galati were obvious and hopeless outsiders, quickly returning to the Second Division. Rapid and Progresul were unlikely losers – both clubs knew success, both were in the shadow of Steaua and Dinamo, so never able to build and keep consistently strong squads, but their lowest point would have been in mid-table, not at the bottom. Unlike the pariahs, FCL Galati, these two fought and may be were a bit unlucky to end in the relegation zone, yet, there they were and Bucharest lost 2 out of 5 First league clubs. The sudden decrease may be described as a decline of Bucharest football, but I am reluctant, largely because, with the exception of Universitatea (Craiova), provincial Romania did not produce any long-lasting strong team. Bucharest was challenged, but not destroyed. There was only an ironic twist, if the names of the relegated are 'interpreted': Rapid was rapidly going down, and Progresul, roughly meaning 'progressive', were actually regressive. However, outside the misfortune of of the particular clubs, no major conclusion of the state of Romanian football could be made.

Wednesday, October 17, 2012

May be defensive play was enough in the championship, but not enough in the Cup tournament. Dinamo (Kiev) did not reach the ½ finals, another indication that even they were not in great shape. Zenit (Leningrad) and Zarya (Voroshilovgrad) were the losing semi-finalists – Zarya, slowly declining after 1972, was consistently well performing in the Cup. Twice a finalists – in 1974 and 1975, now semi-finalists, practically every year they managed to go high. High, but never winning, and this year was no exception – they lost to Torpedo (Moscow). Diamo (Moscow) eliminated Zenit and the final was all-Moscow, opposing the two champions of the short 1976 championships. The final was not a great match, but finals rarely are anyway. Torpedo looked somewhat better and may be unlucky to the specialists, but they failed to score and Dinamo did. True, there was a feeling that he referee robbed Torpedo of a penalty, but then again there goalkeeper failed to clean the ball from a cross in the 17th minute and Dinamo scored.

A. Zarapin helplessly watching the ball crossing the line after the shoot of Kazachenok.

This proved to be the only goal in the final, and Dinamo prevailed. Rightly or wrongly, only goals count, and who scores more wins.

Dinamo (Moscow), somehow grim looking, showing the Cup to the fans.

For Dinamo it was 5th Cup, not bad, but the faces above are ominous – as if the players saw the bitter future. May be Torpedo's players saw their future too... both teams we never champions again as long as USSR lasted and each club managed to add only one Cup in the 1980s. Neither is particluarly successful in post-Soviet Russia... but nobody knew it in 1977, and Dinamo and their fans were happy.

The squad appeared solid – experienced names, some former national team players – Gershkovich, and Dolmatov, some current ones – Pilguy and Minaev, some future ones – Bubnov and Novikov, some respected old hands – Makhovikov and Yakubik, some young promise – Parov and Kazachenok. Something of everything, but no flair, no spark. The team appears rather old-fashioned and behindd the time... may be because of their coach – another well-known and respected, but slightly over the hill oldtimer, Alexander Sevidov. But let not judge the winners.

Let not judge them, because it was not over yet – at the end of the season a brand new challenge was introduced: 'The Cup of the Season', organized by the daily 'Komsomolskaya Pravda'. The champion and the Cup winner were to compete for the prize – in modern terms, it was an early version of now-popular Supercups. Dinamo (Kiev) vs Dinamo (Moscow). Opportunity for a double for both clubs... The match was played in Tbilisi, to the envy of local Dinamo's fans, but in December where else in the USSR? It was one more reason for doubts over the state of Soviet football and particularly Dinamo (Kiev).

A. Minaev (#10) scored for Moscow in the 54th minute. Yurkovsky on his knees... and so was Dinamo (Kiev). Not really outplayed, but lost this match and finished the year with a single trophy.

Double for Dinamo (Moscow):

Oleg Dolmatov, the captain, collects the new cup. Double for Dinamo (Moscow) and, technically, the strongest Soviet team in 1977.

Particularly taciturn looking winners – these team evidently never smiled... standing, from left: Pilguy, Makhovikov, Kazachenok, Sevidov -coach, Maksimenkov, Nikulin, Yakubik, Dolmatov.

Bottom: Gershkovich, Kolesov, Parov, Petrushin, Minaev, Bubnov.

Double is great and so on, but... the goalscorers in both finals were not homegrown stars: Minaev came from Spartak (Moscow) and Kazachenok from Zenit (Leningrad). From the homeboys only Bubnov was showing real progress. Thus, the last great year of Dynamo (Moscow) ended.

May be great for Dinamo (Moscow), but not overall – it was dismal season, especially when international performance is added. But even domestic football alone was dismal – Evgeny Goryansky, one of the better Soviet coaches, titled his article on the finished season 'We continue to wait for something bigger'. Yet, there was hope too – it laid with the juniors. There were bunch of highly talented players, modern in approach and very different from the older generation. They had to grow up, though.

A. Zarapin helplessly watching the ball crossing the line after the shoot of Kazachenok.

This proved to be the only goal in the final, and Dinamo prevailed. Rightly or wrongly, only goals count, and who scores more wins.

Dinamo (Moscow), somehow grim looking, showing the Cup to the fans.

For Dinamo it was 5th Cup, not bad, but the faces above are ominous – as if the players saw the bitter future. May be Torpedo's players saw their future too... both teams we never champions again as long as USSR lasted and each club managed to add only one Cup in the 1980s. Neither is particluarly successful in post-Soviet Russia... but nobody knew it in 1977, and Dinamo and their fans were happy.

The squad appeared solid – experienced names, some former national team players – Gershkovich, and Dolmatov, some current ones – Pilguy and Minaev, some future ones – Bubnov and Novikov, some respected old hands – Makhovikov and Yakubik, some young promise – Parov and Kazachenok. Something of everything, but no flair, no spark. The team appears rather old-fashioned and behindd the time... may be because of their coach – another well-known and respected, but slightly over the hill oldtimer, Alexander Sevidov. But let not judge the winners.

Let not judge them, because it was not over yet – at the end of the season a brand new challenge was introduced: 'The Cup of the Season', organized by the daily 'Komsomolskaya Pravda'. The champion and the Cup winner were to compete for the prize – in modern terms, it was an early version of now-popular Supercups. Dinamo (Kiev) vs Dinamo (Moscow). Opportunity for a double for both clubs... The match was played in Tbilisi, to the envy of local Dinamo's fans, but in December where else in the USSR? It was one more reason for doubts over the state of Soviet football and particularly Dinamo (Kiev).

A. Minaev (#10) scored for Moscow in the 54th minute. Yurkovsky on his knees... and so was Dinamo (Kiev). Not really outplayed, but lost this match and finished the year with a single trophy.

Double for Dinamo (Moscow):

Oleg Dolmatov, the captain, collects the new cup. Double for Dinamo (Moscow) and, technically, the strongest Soviet team in 1977.

Particularly taciturn looking winners – these team evidently never smiled... standing, from left: Pilguy, Makhovikov, Kazachenok, Sevidov -coach, Maksimenkov, Nikulin, Yakubik, Dolmatov.

Bottom: Gershkovich, Kolesov, Parov, Petrushin, Minaev, Bubnov.

Double is great and so on, but... the goalscorers in both finals were not homegrown stars: Minaev came from Spartak (Moscow) and Kazachenok from Zenit (Leningrad). From the homeboys only Bubnov was showing real progress. Thus, the last great year of Dynamo (Moscow) ended.

May be great for Dinamo (Moscow), but not overall – it was dismal season, especially when international performance is added. But even domestic football alone was dismal – Evgeny Goryansky, one of the better Soviet coaches, titled his article on the finished season 'We continue to wait for something bigger'. Yet, there was hope too – it laid with the juniors. There were bunch of highly talented players, modern in approach and very different from the older generation. They had to grow up, though.

Monday, October 15, 2012

The Ovsepyan case appeared at the end of the year, when the season was over. Back in the early spring the marathon was about to begin and naturally there was no gloom, but hope. Hope was short-lived: the return to normal structure quickly immediately led to the triumph of stubborn practices and ills. It could be said that 1977 was the lowest point of Soviet football in the decade. Everything was painfully familiar – the champion, the relegated, the bulk of mid-table unambitious clubs, the low scoring, the love of security in tied games, in which everybody got the 'sacred' point. The end of forced winning, characteristic of the previous seasons, was almost greeted with a roar by all clubs: once there was no limit to ties, everyone was happy... only three clubs ended with fewer than 10 ties, that is with less than 1/3 of the total seasonal matches tied. On the other side were the 'record makers': it was also tied race – Dinamo (Moscow), Kairat (Alma-Ata), Neftchi (Baku), and CSKA (Moscow) ended 17 of their matches tied. The champions, Dinamo (Kiev), finished exactly 50% of their games tied. Winning was obviously not the goal – only 4 clubs finished with more than 10 wins. Not a single club managed to come close to 2-goal average per game: the champions were best with 51 goals, or 1.7 goals per match average. But the bronze medalists, Torpedo (Moscow), represented best the prevailing attitudes: they scored measly 30 goals through the season, 1 per game. In fact, only 7 clubs ended with 30 or more goals this season – not even half the league. Half the league fretted over relegation, though – three points were the whole difference between 8th and 15th place. The best goalscorer was summing the misery: Oleg Blokhin was top goalscorer for 5th time already. He scored 17 goals. He was consistent no doubt, and already hold the record – nobody else was so many time the best scorer in USSR, but in the all-time table he was 34th before the season and climbed to 20th place after the end. Only 18 players in the history of Soviet football scored 100 or more goals and none of them was an active player by 1977. Among the active players, barring Blokhin, none was really expected to make the milestone mark of 100 – some were too old, like Banishevsky, others - so far behind, that 50 goals was more or less the expected maximum.

Anatoly Banishevsky, one of brighest Soviet stars of the 1960s. Regular national team player, formidable centreforward, goalscorer... and almost forgotten name by 1977, when he was not yet 32-years old. Playing for the small Neftci (Baku) and suffering injuries did not help, of course, but his 71 goals total before the 1977-season were not very impressive. He did not add much during the championship... and his playing days were rapidly diminishing.

Down in the table were mostly familiar inhabitants – Krylya Sovetov (Kuybyshev) were hopeless: they managed to win only 2 matches and collected a total of 11 points. Last place and relegation was certain almost from the start of the season, and they returned to second division after two years among the best. The second relegated club was a bit of a surprise: Karpaty (Lvov) were 4th in 1976, reaching a UEFA Cup spot. Now they sunk to 15th place.

A tired and increasingly aging team, Karpaty slipped down. Gone were the days when Kozinkevich was playing for the national team... and seemingly no new talent was pushing forward. There was only one name interesting... in retrospect: A. Bal, 18-years old. He was to become famous, but not with Karpaty.

Another club also slipped down and barely escaped relegation, finishing 14th with 1 point more than unlucky Karpaty: CSKA (Moscow). This was alarming – Moscow football surely was getting worse. Spartak playing in Second Division and now another 'big name' fighting for mere survival. CSKA was on slippery-slope for a few years already. It was even confusing – there were good players in the squad, some national team regulars: Astapovsky, Olshansky, Nazarenko, Morozov. Tarkhanov, Saukh, Radaev, and Shvetzov were considered very promising... Kopeykin, Nikonov, Chesnokov were experienced and no strangers to the national team in the recent past, yet, the 'chemistry' was not there. Once a mighty team, the Army was not even middle-of-the-road club now.

Above the outsiders were vast bulk of so-so clubs, normally occupying mid-table, occasionally struggling for survival, most of the time not and satisfied with quiet existence.

Zenit (Leningrad) represents this group best: they finished 10th. No surprises, no great moments, rather gray and ordinary, even there mass production Adidas kits. Zenit apparently had limited resources – something a bit strange for the second most important Soviet city – and was unable to build strong squad. Better players were leaving to join other clubs, even second division ones, as was the case of Zinchenko and Khromchenkov. Most of the team were experienced, but hardly impressive players. The new 'star' was their 28-years old striker Markin – hardly a future promise at his age. The only noticeable youngster was Redkous, and it was almost certain that he was not going to last long with Zenit. In fact, the only big name was the coach German Zonin, who made small Zarya (Voroshilovgrad) surprise champions in 1972. How good a coach Zonin was is really impossible to judge: true, Zenit had no means to build strong team, but seemingly the presence of Zonin had no impact on performance.

And like Zenit were most of the clubs in the league. The 'best' among them this year was Lokomotiv (Moscow), finishing sixth. Sixth, but just a few players of some importance, capable of 32 points from 30 matches.

Which left the 'usual suspects' at the very top – Shakter (Donetzk), Dinamo (Moscow), Torpedo (Moscow), Dinamo (Tbilisi), and Dinamo (Kiev). Head and shoulders above the rest they were not, but somewhat better – yes. Shakter was steady, so was Dinamo (Tbilisi), and the champions of the two 1976 championships – Torpedo and Dinamo Moscow – were seemingly running on the steam of the last year. At the end, none was able to really challenge Dinamo (Kiev). Torpedo ended with bronze medals.

Standing from left: Mironov, Sakharov, Khrabrostin (?), Buturlakin, Khlopotnov, Prigoda, Zarapin

Kneeling: Petrenko, Kruglov, Yurin, Filatov.

Good season for Torpedo – in their own terms, for the predicament of the club was to be always modestly behind the formidable Moscow's trio of Dinam, Spartak, and CSKA. The golden years of the club were long gone with the 1960s and this was a bit more than expected from them. Sure, they had solid team, with some men occasionally included in the national team – Prigoda and Sakharov – and plenty of well respected players, like Yurin, Khrabrostin, Buturlakin, Kruglov, Petrenko, Filatov, but at a glance they were not champions material. Upper-half of the table, but no more. So, it was a success, however unimpressive, and practically the last season Torpedo played major role in Soviet football.

The silver medalists were another story. Dinamo (Tbilisi) were always among the best Soviet clubs and were known for their technical, attacking style. Perhaps they were the most pleasant to watch Soviet team, which may be was their undoing as well, for artistic flair rarely succeeded in the dull Soviet football, aiming at killing the game so to manage a tie and collect a point. As most artistic teams, Dinamo were moody, which was not helping either – they were capable of great match one week only to collapse in the next. Their inconsistency affected the whole judgment of them - perhaps the Georgians were the most criticized players, always 'failing expectations', included with suspicion in the national team, and dismissed at the first mistake.

Sitting in front, from left: V. Daraselia, V. Gutzaev, D. Kipiani, R. Shengelia, R. Chelebadze.

Middle row: T. Kostava, G. Machaidze, S. Metreveli – assistant coach, N. Dzapshila – chief of the team, N. Akhalkatzi – coach, S. Kutivadze – assistant coach, M. Machaidze, V. Kopaleishvili.

Top row: O. Gabelia, D. Mudzhiri, A. Chivadze, Sh. Khinchagashvili, P. Kanteladze, N. Khizanishvili, V. Koridze, D. Gogia.

Well known squad already in the USSR, with plenty of talent and few players establishing themselves solidly in the national team, particularly David Kipiani, the magnificent striker, and the central defender Alexander Chivadze. Young talent was plentiful – Shengelia, Daraselia, Gabelia, Mudzhiri. Nodar Akhalkatzi carefully selected great squad, which was just not ripe yet, but had enormous talent and its days were coming soon. But not in 1977 – the team was good enough for second place, yet, not really challenged Dinamo (Kiev), trailing 4 points behind. It was still a team for the future.

Which left the familiar Dinamo (Kiev) once again on top. The numbers of the champions were a bit strange: Dinamo ended with confident 4-point lead. They lost only one match and their defensive record is perhaps unmatched in the history of Soviet football: they allowed only 12 goals in 30 games. Of course, they won the most matches – 14 – and scored most goals – 51. But... they finished half of their games in draws, which amounted to uncomfortable fact: the champions failed to win 16 games, more than ½ of the total. Their scoring was hardly great as well... in the rather pedestrian Soviet league of this vintage, Dinamo was unable to really dominate. It looked like the team struggled, and hints of that are detectable in the words of Dinamo's captain Victor Kolotov after the end of the season: quite a few teammates were described as underperforming, if not plainly declining, but none was mentioned as improving, let alone as revelation.

8th time champions: bottom from left: P. Slobodyan, S. Reshko, V. Bessonov, V. Troshkin, V. Muntyan, V. Onishtchenko.

Middle row: V. Lobanovsky – coach, V. Lozinsky, L. Buryak, O. Blokhin, A. Berezhnoy, V. Berkovsky – team doctor, V. Malyuta – team doctor, M. Koman – chief coach, responsible for 'educational work'.

Third row: V. Kolotov, M. Fomenko, V. Matvienko, V. Veremeev, V. Yurkovsky, A. Konkov, E. Evlantiev – masseur.

At a glance, very familiar team – all heroes, winning the Cup Winners Cup in 1975, are here. They were here and that suggested a problem: inevitably aging. Hints of transitional struggle are detectable: Lobanovsky was no fool and some young players were already included, pushing away older stars. One thing was certain: Dinamo invested greatly in their youth system and every year a bunch of youngsters were included in the first team. But so far there was no obvious great talent – rather promising players, who most often stayed on the bench. Lobanovsky was no fool, but he was seemingly hesitating to make radical changes. The team was quite defensively oriented after 1975 – very crowded midfield, two strikers, practically going down to one. Goalkeeping problem loomed... Evgeny Rudakov was listed in the team at the beginning of the season, but the veteran suffered from injuries and did not play. His absence opened a problem for many years – almost to mid-1980s. As often happens, replacing goalkeeper, who was a staple practically 'forever' is very difficult, for such players are well remembered and somehow every new goalie fails short in comparesement. It is universal problem, and Dinamo did not escape it – Yurkovsky played this season, but he was to be replaced soon. His replacement too, and so on. For now, it was kind of a weak post... not exactly helped by the state of defense, where Matvienko was clearly fading away. So was Fomenko. Reshko was still the fighter, but no more than that, and at his age it was unlikely he was to become better. He was not exactly the player fitting Lobanovsky's ideas of defenders – Konkov was moved back from midfield to defense, which worked to some extend, but robbed midfield of creativity. The right full-back continued to be a problem – Troshkin was no longer the same great runner, able to cover the whole field, playing as a full-back, mid-fielder, and doubling as a winger all at once. Looks like that Troshkin preferred a return to his original position as defensive midfielder, especially since Konkov was moved back to defense and the position was open – and needed. Lozinsky was tried at the right full-back position, and he showed considerable promise – yet, he was somehow not the player Lobanovsky saw in his dreams. There was one more youngster, who increasingly was becoming regular – Berezhnoy. He was to become much bigger name yet, but he was central defender, so the right flank remained more or less open sore. And with Matvienko no longer the same, the other flank was going to be a problem too... The problems in midfield were the exact opposite – too many players. It was good to have long bench in case of injuries – and Kolotov and Muntyan missed many games because of them – but when everyone was healthy it was plain trouble: Kolotov, Veremeev, Muntyan, Buryak... add Konkov and Troshkin, who had midfielder habits, and constantly moved there. The young talent Sergey Baltacha was also midfielder (Lobanovsky moved him back to central defense later), and finally – the greatest talent at hand, Bessonov. It was clear that he had a place among the regular starters, but where... Midfield was so crowded, Bessonov had to play right full back on occasion. At the end, the crowded line developed tensions and problems – Veremeev and Buryak somewhat underperformed, and Buryak was beginning to clash with Lobanovsky. There was chronic problem with creativity, so Muntyan continued to be vital for the team as playmaker. When he was out, the team suffered, but Muntyan was nearing the end of his playing days. Crowded midfield meant reduced attack – as before, Lobanovsky rarely used typical centerforward, but now even two wingers were becoming a luxury – there was no place for a second winger anymore... on top of it Onishtchenko was losing form with age. He was no longer the fiery deadly striker and very likely was in conflict with Lobanovsky. Blokhin was becoming the sole striker, which was a problem detected at least an year ago: as a typical left winger, Blokhin was not exactly efficient when asked to operate in the center and the right half of the field, but as a lonely striker, he had to go friquently there. Roving striker was Dinamo really needed for their style, but they had classic left winger. They won the title, but it was quite obvious hat massive changes had to be made and soon – Dinamo was not very convincing this year. It looked like Lobanovsky started building a new team, but it was at very early stage. In fact, most of the youngsters included did not become regulars and soon were dismissed to other clubs. The future team was very rudimentary at this point – Baltacha, Bessonov, Brezhnoy, and Hapsalis. Dinamo was able to win the Soviet championship, and therefore to have enough 'breathing space' for searching for new great squad, but... to a point, their winning was due to the weakness of the competition. The whole Soviet football was down, but not without hope: there was talented, still very young generation growing up. Still juniors, but coming fast. As for 'old' Dinamo, there was one significant record made along with the 8th title: Vladimir Muntyan became the first Soviet player 7 times champion – his first title with Dinamo was in 1966. Football is strange – Muntyan is hardly among the top all-time Soviet stars, but he achieved much more than most of the really great players.

Tellingly, a photo of Dinamo (Kiev) defending was chosen to celebrate their new title – in white from left: M. Fomenko, S. Reshko, V. Yurkovsky, V. Lozinsky braking another attack of Dinamo (Tbilisi).

Anatoly Banishevsky, one of brighest Soviet stars of the 1960s. Regular national team player, formidable centreforward, goalscorer... and almost forgotten name by 1977, when he was not yet 32-years old. Playing for the small Neftci (Baku) and suffering injuries did not help, of course, but his 71 goals total before the 1977-season were not very impressive. He did not add much during the championship... and his playing days were rapidly diminishing.

Down in the table were mostly familiar inhabitants – Krylya Sovetov (Kuybyshev) were hopeless: they managed to win only 2 matches and collected a total of 11 points. Last place and relegation was certain almost from the start of the season, and they returned to second division after two years among the best. The second relegated club was a bit of a surprise: Karpaty (Lvov) were 4th in 1976, reaching a UEFA Cup spot. Now they sunk to 15th place.

A tired and increasingly aging team, Karpaty slipped down. Gone were the days when Kozinkevich was playing for the national team... and seemingly no new talent was pushing forward. There was only one name interesting... in retrospect: A. Bal, 18-years old. He was to become famous, but not with Karpaty.

Another club also slipped down and barely escaped relegation, finishing 14th with 1 point more than unlucky Karpaty: CSKA (Moscow). This was alarming – Moscow football surely was getting worse. Spartak playing in Second Division and now another 'big name' fighting for mere survival. CSKA was on slippery-slope for a few years already. It was even confusing – there were good players in the squad, some national team regulars: Astapovsky, Olshansky, Nazarenko, Morozov. Tarkhanov, Saukh, Radaev, and Shvetzov were considered very promising... Kopeykin, Nikonov, Chesnokov were experienced and no strangers to the national team in the recent past, yet, the 'chemistry' was not there. Once a mighty team, the Army was not even middle-of-the-road club now.

Above the outsiders were vast bulk of so-so clubs, normally occupying mid-table, occasionally struggling for survival, most of the time not and satisfied with quiet existence.

Zenit (Leningrad) represents this group best: they finished 10th. No surprises, no great moments, rather gray and ordinary, even there mass production Adidas kits. Zenit apparently had limited resources – something a bit strange for the second most important Soviet city – and was unable to build strong squad. Better players were leaving to join other clubs, even second division ones, as was the case of Zinchenko and Khromchenkov. Most of the team were experienced, but hardly impressive players. The new 'star' was their 28-years old striker Markin – hardly a future promise at his age. The only noticeable youngster was Redkous, and it was almost certain that he was not going to last long with Zenit. In fact, the only big name was the coach German Zonin, who made small Zarya (Voroshilovgrad) surprise champions in 1972. How good a coach Zonin was is really impossible to judge: true, Zenit had no means to build strong team, but seemingly the presence of Zonin had no impact on performance.

And like Zenit were most of the clubs in the league. The 'best' among them this year was Lokomotiv (Moscow), finishing sixth. Sixth, but just a few players of some importance, capable of 32 points from 30 matches.

Which left the 'usual suspects' at the very top – Shakter (Donetzk), Dinamo (Moscow), Torpedo (Moscow), Dinamo (Tbilisi), and Dinamo (Kiev). Head and shoulders above the rest they were not, but somewhat better – yes. Shakter was steady, so was Dinamo (Tbilisi), and the champions of the two 1976 championships – Torpedo and Dinamo Moscow – were seemingly running on the steam of the last year. At the end, none was able to really challenge Dinamo (Kiev). Torpedo ended with bronze medals.

Standing from left: Mironov, Sakharov, Khrabrostin (?), Buturlakin, Khlopotnov, Prigoda, Zarapin

Kneeling: Petrenko, Kruglov, Yurin, Filatov.

Good season for Torpedo – in their own terms, for the predicament of the club was to be always modestly behind the formidable Moscow's trio of Dinam, Spartak, and CSKA. The golden years of the club were long gone with the 1960s and this was a bit more than expected from them. Sure, they had solid team, with some men occasionally included in the national team – Prigoda and Sakharov – and plenty of well respected players, like Yurin, Khrabrostin, Buturlakin, Kruglov, Petrenko, Filatov, but at a glance they were not champions material. Upper-half of the table, but no more. So, it was a success, however unimpressive, and practically the last season Torpedo played major role in Soviet football.

The silver medalists were another story. Dinamo (Tbilisi) were always among the best Soviet clubs and were known for their technical, attacking style. Perhaps they were the most pleasant to watch Soviet team, which may be was their undoing as well, for artistic flair rarely succeeded in the dull Soviet football, aiming at killing the game so to manage a tie and collect a point. As most artistic teams, Dinamo were moody, which was not helping either – they were capable of great match one week only to collapse in the next. Their inconsistency affected the whole judgment of them - perhaps the Georgians were the most criticized players, always 'failing expectations', included with suspicion in the national team, and dismissed at the first mistake.

Sitting in front, from left: V. Daraselia, V. Gutzaev, D. Kipiani, R. Shengelia, R. Chelebadze.

Middle row: T. Kostava, G. Machaidze, S. Metreveli – assistant coach, N. Dzapshila – chief of the team, N. Akhalkatzi – coach, S. Kutivadze – assistant coach, M. Machaidze, V. Kopaleishvili.

Top row: O. Gabelia, D. Mudzhiri, A. Chivadze, Sh. Khinchagashvili, P. Kanteladze, N. Khizanishvili, V. Koridze, D. Gogia.

Well known squad already in the USSR, with plenty of talent and few players establishing themselves solidly in the national team, particularly David Kipiani, the magnificent striker, and the central defender Alexander Chivadze. Young talent was plentiful – Shengelia, Daraselia, Gabelia, Mudzhiri. Nodar Akhalkatzi carefully selected great squad, which was just not ripe yet, but had enormous talent and its days were coming soon. But not in 1977 – the team was good enough for second place, yet, not really challenged Dinamo (Kiev), trailing 4 points behind. It was still a team for the future.

Which left the familiar Dinamo (Kiev) once again on top. The numbers of the champions were a bit strange: Dinamo ended with confident 4-point lead. They lost only one match and their defensive record is perhaps unmatched in the history of Soviet football: they allowed only 12 goals in 30 games. Of course, they won the most matches – 14 – and scored most goals – 51. But... they finished half of their games in draws, which amounted to uncomfortable fact: the champions failed to win 16 games, more than ½ of the total. Their scoring was hardly great as well... in the rather pedestrian Soviet league of this vintage, Dinamo was unable to really dominate. It looked like the team struggled, and hints of that are detectable in the words of Dinamo's captain Victor Kolotov after the end of the season: quite a few teammates were described as underperforming, if not plainly declining, but none was mentioned as improving, let alone as revelation.

8th time champions: bottom from left: P. Slobodyan, S. Reshko, V. Bessonov, V. Troshkin, V. Muntyan, V. Onishtchenko.

Middle row: V. Lobanovsky – coach, V. Lozinsky, L. Buryak, O. Blokhin, A. Berezhnoy, V. Berkovsky – team doctor, V. Malyuta – team doctor, M. Koman – chief coach, responsible for 'educational work'.

Third row: V. Kolotov, M. Fomenko, V. Matvienko, V. Veremeev, V. Yurkovsky, A. Konkov, E. Evlantiev – masseur.

At a glance, very familiar team – all heroes, winning the Cup Winners Cup in 1975, are here. They were here and that suggested a problem: inevitably aging. Hints of transitional struggle are detectable: Lobanovsky was no fool and some young players were already included, pushing away older stars. One thing was certain: Dinamo invested greatly in their youth system and every year a bunch of youngsters were included in the first team. But so far there was no obvious great talent – rather promising players, who most often stayed on the bench. Lobanovsky was no fool, but he was seemingly hesitating to make radical changes. The team was quite defensively oriented after 1975 – very crowded midfield, two strikers, practically going down to one. Goalkeeping problem loomed... Evgeny Rudakov was listed in the team at the beginning of the season, but the veteran suffered from injuries and did not play. His absence opened a problem for many years – almost to mid-1980s. As often happens, replacing goalkeeper, who was a staple practically 'forever' is very difficult, for such players are well remembered and somehow every new goalie fails short in comparesement. It is universal problem, and Dinamo did not escape it – Yurkovsky played this season, but he was to be replaced soon. His replacement too, and so on. For now, it was kind of a weak post... not exactly helped by the state of defense, where Matvienko was clearly fading away. So was Fomenko. Reshko was still the fighter, but no more than that, and at his age it was unlikely he was to become better. He was not exactly the player fitting Lobanovsky's ideas of defenders – Konkov was moved back from midfield to defense, which worked to some extend, but robbed midfield of creativity. The right full-back continued to be a problem – Troshkin was no longer the same great runner, able to cover the whole field, playing as a full-back, mid-fielder, and doubling as a winger all at once. Looks like that Troshkin preferred a return to his original position as defensive midfielder, especially since Konkov was moved back to defense and the position was open – and needed. Lozinsky was tried at the right full-back position, and he showed considerable promise – yet, he was somehow not the player Lobanovsky saw in his dreams. There was one more youngster, who increasingly was becoming regular – Berezhnoy. He was to become much bigger name yet, but he was central defender, so the right flank remained more or less open sore. And with Matvienko no longer the same, the other flank was going to be a problem too... The problems in midfield were the exact opposite – too many players. It was good to have long bench in case of injuries – and Kolotov and Muntyan missed many games because of them – but when everyone was healthy it was plain trouble: Kolotov, Veremeev, Muntyan, Buryak... add Konkov and Troshkin, who had midfielder habits, and constantly moved there. The young talent Sergey Baltacha was also midfielder (Lobanovsky moved him back to central defense later), and finally – the greatest talent at hand, Bessonov. It was clear that he had a place among the regular starters, but where... Midfield was so crowded, Bessonov had to play right full back on occasion. At the end, the crowded line developed tensions and problems – Veremeev and Buryak somewhat underperformed, and Buryak was beginning to clash with Lobanovsky. There was chronic problem with creativity, so Muntyan continued to be vital for the team as playmaker. When he was out, the team suffered, but Muntyan was nearing the end of his playing days. Crowded midfield meant reduced attack – as before, Lobanovsky rarely used typical centerforward, but now even two wingers were becoming a luxury – there was no place for a second winger anymore... on top of it Onishtchenko was losing form with age. He was no longer the fiery deadly striker and very likely was in conflict with Lobanovsky. Blokhin was becoming the sole striker, which was a problem detected at least an year ago: as a typical left winger, Blokhin was not exactly efficient when asked to operate in the center and the right half of the field, but as a lonely striker, he had to go friquently there. Roving striker was Dinamo really needed for their style, but they had classic left winger. They won the title, but it was quite obvious hat massive changes had to be made and soon – Dinamo was not very convincing this year. It looked like Lobanovsky started building a new team, but it was at very early stage. In fact, most of the youngsters included did not become regulars and soon were dismissed to other clubs. The future team was very rudimentary at this point – Baltacha, Bessonov, Brezhnoy, and Hapsalis. Dinamo was able to win the Soviet championship, and therefore to have enough 'breathing space' for searching for new great squad, but... to a point, their winning was due to the weakness of the competition. The whole Soviet football was down, but not without hope: there was talented, still very young generation growing up. Still juniors, but coming fast. As for 'old' Dinamo, there was one significant record made along with the 8th title: Vladimir Muntyan became the first Soviet player 7 times champion – his first title with Dinamo was in 1966. Football is strange – Muntyan is hardly among the top all-time Soviet stars, but he achieved much more than most of the really great players.

Tellingly, a photo of Dinamo (Kiev) defending was chosen to celebrate their new title – in white from left: M. Fomenko, S. Reshko, V. Yurkovsky, V. Lozinsky braking another attack of Dinamo (Tbilisi).

Saturday, October 13, 2012

Before moving to First Division an extraordinary event must be mentioned: the case of Avetis Ovsepyan. A little known goalkeeper was subject for a full page article in the 'Football-Hockey' weekly – it was a nasty piece of work, for Ovsepyan came back from the USA. A story of a traitor. Such articles appeared rarely – only when somebody, who run away from 'paradise' came back. The purpose was 'educational': to show the ordinary citizens how bad is the Capitalist world and how great their own Communist state. The returnees had no choice, but to subject themselves to public self-flagellation and beg for forgiveness, but the required humiliation was not at all the end of their troubles: normally, some were jailed at least for awhile, almost certainly barred from their professions, and subjected to suspicion and harassment. Tainted for life, not trusted, and constantly reminded of their crime. At first the case of Ovsepyan looked 'standard' – when he returned, an article was published, disguised as an 'honest' interview with him in the newspaper 'Communist', Erevan. The article appeared immediately in 'Football-Hockey' as well, telling a horror story – the capitalist world had no place for the young Armenian. He was unable to find work as an 'mechanical engineer' and only with great difficulties as a football player. It was the football world, which was presented in more details: Ovsepyan arrived in Los Angeles and the NASL club, Los Angeles Aztecs simply turned him away. He looked around, thinking that for a former first-division player would be appreciated, but no, he was not. Eventually, he was hired by Los Angeles Skyhawks, playing in the American Soccer League. In European terms, ASL approximates third division... big drop down, but there was worse: essentially, Ovsepyan's story tells of coldness, merciless exploitation, loneliness, and even lack of professionalism in the club. The teammates were rag-tag company from many countries, thinking only of money and not giving a damn about the game. They met only for the duration of training and playing, total strangers to each other. Money were symbolic – Ovsepyan received a total of $1600 for 4 months. At the end he was not able to take it anymore and decided to come back. Hence, the whole horror story had to be told, in theory initiated by the player himself. The masses were to know how bad was 'over the hill' and never to think of going there – that was the real purpose of the article and Ovsepyan served the purpose well, even calling himself traitor (although, not directly – there is no actual voice of the offender in the article. Everything is retold by the journalists, so according to them Ovsepyan called himself a traitor.) The traitor missed the good Soviet life, he missed his birthplace. Typical... under Capitalism there is no life.

The story does not tell really much about Ovsepyan, so the initial impression was that he run away – something very rare, especially for Soviet football players. At least no known name ever did, although some were suspected of harboring the thought – and measures were taken, namely, not to permit them to travel abroad for visiting matches. But it turned out Ovsepyan did not run away – his whole family was permitted to emigrate and he was with his parents and brother. Relatives, living in Los Angeles, sponsored them and after brief stay in Italy the family arrived in Los Angeles. Of course emigration was not permitted in USSR, but during the 1970s individual cases were permitted to leave – mostly Jewish, some Armenians, occasional other non-Russians. Such people did nothing illegal, but the very fact they wanted out was remembered, considered a form of treachery, and, therefore, if someone decided to come back, they were treated just like those who originally defected. Of course, the article says nothing about that, as well as another detail is omitted: Ovsepyan was born in Tehran, Iran, in 1954. Apparently, his family emigrated from Iran to USSR, so they were at best only naturalized Soviet citizens – not native ones. But Avanes grew up in Erevan, knew no other country or lifestyle that the Soviet one. He trained football in Erevan, but also studied and eventually reached the first team of Ararat and looks like studied engineering in the local university. However, this was not so important at first: the article suggests only standard propaganda and once the 'traitor' serves his purpose, he was to disappear for good from public eye. Looking from the distance of time, the whole thing appear in different light: as a clever effort for full rehabilitation of 'the traitor'. The Armenians are crafty people and, in terms of USSR, Erevan is periphery. Many things may happen in the periphery, away from watchful central eyes. Ovsepyan appeared in Ararat's team list in 1978 and played for the club until 1981. This makes him the second Soviet player, who was able to play professionally abroad – the first is Vassilis Hadzipanagis. True, Ovsepyan was permit to emigrate just to play professional football, but he did. Not much, but he did. It is difficult to find material about his US playing career, but there are few bits – now called Avetis Hovsepian, a new goalkeeper appeared as a reserve player in LA Skyhawks. Hovsepian evidently was no revelation... even in the pathetic US football. Now it becomes clearer why he had troubles: he was simply no good. His record plainly says that: he was with Ararat only in 1976, when he played a total of 9 matches. Between 1978 and 1980 he appeared in 22 more, all of them during the 1978 season. Valuable player he was not, but there was something else, may be explaining his rapid and unusual rehabilitation in Soviet football: after the retirement of great Alyosha Abramyan, Ararat experienced acute goalkeeping crisis for years. May the club itself applied some pressure on officials, hoping to find a remedy for its problem. Four goalkeepers were listed in 1978, none long-lasting or memorable. More names followed in the next years. May be Ovsepyan returned in lucky moment and the club's crisis helped him. May be , may be not. The real point is still different now: he was the second Soviet player who played abroad, and the first one, who after playing foreign football appeared again in the Soviet championship. No picture of the player can be unearthed, though...

The story does not tell really much about Ovsepyan, so the initial impression was that he run away – something very rare, especially for Soviet football players. At least no known name ever did, although some were suspected of harboring the thought – and measures were taken, namely, not to permit them to travel abroad for visiting matches. But it turned out Ovsepyan did not run away – his whole family was permitted to emigrate and he was with his parents and brother. Relatives, living in Los Angeles, sponsored them and after brief stay in Italy the family arrived in Los Angeles. Of course emigration was not permitted in USSR, but during the 1970s individual cases were permitted to leave – mostly Jewish, some Armenians, occasional other non-Russians. Such people did nothing illegal, but the very fact they wanted out was remembered, considered a form of treachery, and, therefore, if someone decided to come back, they were treated just like those who originally defected. Of course, the article says nothing about that, as well as another detail is omitted: Ovsepyan was born in Tehran, Iran, in 1954. Apparently, his family emigrated from Iran to USSR, so they were at best only naturalized Soviet citizens – not native ones. But Avanes grew up in Erevan, knew no other country or lifestyle that the Soviet one. He trained football in Erevan, but also studied and eventually reached the first team of Ararat and looks like studied engineering in the local university. However, this was not so important at first: the article suggests only standard propaganda and once the 'traitor' serves his purpose, he was to disappear for good from public eye. Looking from the distance of time, the whole thing appear in different light: as a clever effort for full rehabilitation of 'the traitor'. The Armenians are crafty people and, in terms of USSR, Erevan is periphery. Many things may happen in the periphery, away from watchful central eyes. Ovsepyan appeared in Ararat's team list in 1978 and played for the club until 1981. This makes him the second Soviet player, who was able to play professionally abroad – the first is Vassilis Hadzipanagis. True, Ovsepyan was permit to emigrate just to play professional football, but he did. Not much, but he did. It is difficult to find material about his US playing career, but there are few bits – now called Avetis Hovsepian, a new goalkeeper appeared as a reserve player in LA Skyhawks. Hovsepian evidently was no revelation... even in the pathetic US football. Now it becomes clearer why he had troubles: he was simply no good. His record plainly says that: he was with Ararat only in 1976, when he played a total of 9 matches. Between 1978 and 1980 he appeared in 22 more, all of them during the 1978 season. Valuable player he was not, but there was something else, may be explaining his rapid and unusual rehabilitation in Soviet football: after the retirement of great Alyosha Abramyan, Ararat experienced acute goalkeeping crisis for years. May the club itself applied some pressure on officials, hoping to find a remedy for its problem. Four goalkeepers were listed in 1978, none long-lasting or memorable. More names followed in the next years. May be Ovsepyan returned in lucky moment and the club's crisis helped him. May be , may be not. The real point is still different now: he was the second Soviet player who played abroad, and the first one, who after playing foreign football appeared again in the Soviet championship. No picture of the player can be unearthed, though...

Wednesday, October 10, 2012

Spartak Moscow, the winners of the championship, deserve separate narrative.

Spartak Moscow was ailing since 1970, declining steadily until the unthinkable happened – relegation. The fact of actual relegation surprised even the fans, for so old and revered club most likely was to be salvaged by some scheme (expansion of the league, most likely). According to the club's lore, the club itself proudly refused to be saved and preferred to play fair game and sink in the second division. But repairs started at once – curiously, at the time Spartak lacked a 'sponsor' – that is, was not attached to any institution, something almost impossible in USSR. That was the reason for the decline as well – no money and no strong administration. On spirit alone future did not look bright – and 'sponsor' was found: the Minsitry of Civil Aviation. The first step of recovery was bringing back from retirement the legend of Spartak and Soviet football Nickolay Starostin. Starostin did not like the idea at first, but eventually agreed to become 'Director of the team', a managerial position in the European, not the English sense. His equally famous brother Andrey Starostin suggested a coach: the well known, but not easy to work with Konstantin Beskov. Bringing Beskov to Spartak was not easy: he represented the arch-enemy Dinamo (Moscow), so 'philosophy' as at stake, but the real problem was the fact that Dinamo belonged to the Ministry of the Interior, the Police, and Beskov was not only employed there, but was a full Colonel, which the Police was not willing to free, although he was not coaching at the time. The Minister of Civil Aviation had to pull rank... the commercial aviation of USSR was governed by no less but a Marshal! It took a Marshal to get a Colonel – the Ministry of the Interior did the favour to Marshall Bugaev. But it was not enough – Beskov did not want to coach Spartak and only the severe order of the boss of the Moscow Communist Party made him change his mind.