Kaiafas came, however briefly, to fame when another player, a big star, stepped down. Luigi Riva retired in 1976.

It was not grand retirement…it was not in ‘good style’, it was not even official. Gigi Riva was 32 years old and heavily injured. His Cagliari suffered as well and was relegated. And that was the end of one of the biggest stars of the late 1960s and much loved player. Riva was nicknamed ‘Rombo di Tuono’ (Roar of Thunder) for a good reason: he was powerful, fearless striker, equally at home in the air, literally fighting burly defenders in the penalty area, or running from the wing. His shot was murderous.

Number 11 forever and looking like British striker against Juventus.

Riva was very skilful for a ‘physical’ player – the ball had no secrets for him.

And all ended with roaring stands and Riva triumphal after another goal.

He knew scoring allright… 3 times Italian goalscorer was quite something in the catenaccio land. Between 1961 and 1976 Gigi played 337 matches in which he scored 169 goals. The numbers would have been higher, if not for his many injuries keeping him out of the field quite too often. And at the end it was an injury retiring him. With Riva a whole era ended, whole set of attitudes – loyalty was getting increasingly thing of the past by mid-70s: players increasingly were changing clubs, following better pay. Riva was representative of the old ways: he played for only two clubs – Legnano (1961-62: 22 matches and 6 goals) and from there he moved to Cagliari, where he stayed to the end, eventually becoming Italian champion, his only title. That is, for a so big star, Riva played for relatively small club, having no real opportunity to win trophies. But he stayed and more than that – he declined an offer from Juventus in 1973. Can you imagine present day player declining an offer from Juventus? Declining more money and more titles, and possible bigger transfers after that? But Gigi Riva was from another time, although it should be mentioned that Cagliari paid him handsomely for the times, so money was not big temptation – loyalty is loyalty, but Riva was the big fish in Caglairi; in Juventus he had to fight for a place in the team with other – and younger – big names.

Of course, Riva was national team player – for almost 10 years. Between 1965 and 1974 he appeared in 42 matches and scored 35 goals. Perhaps his best year was 1970 – he was on top of his form and Italy played very good at the World Cup, finishing second to fantastic Brazil.

In Mexico, 1970 – Riva tackled by Bertie Fogts. Riva and Italy won a very tough game and eliminated the Germans. Alas, Vogts was denied only temporary – he became World champion in 1974; Riva never reached the very top of the world… 1974 was more than anticlimactic: it was disgrace. Italy played terribly, Riva was a pale shadow of himself, as everybody else in the team, and was never invited to the national team again. His national team career ended badly and his club career followed the same unlucky pattern… Cagliari was relegated in 1976. Bad luck continued… for the next two years Riva tried to comeback unsuccessfully. Age and chronic injuries worked against his will and he officially retired in 1978. But his last match was played in 1976 and for all practical purposes his game finished exactly then. Bad luck, but it was not to condemn Gigi Riva to oblivion. He is remembered fondly and rightly so – what a player he was!

Wednesday, May 30, 2012

Monday, May 28, 2012

The new reality was even more obvious in the last big award: the Golden Shoe. Nobody expected an Italian goalscorer to win it – after all whole teams hardly scored 20 goals in a season ever there. Nobody expected a Spaniard to win either. Or British player. Those were tough championships with vicious defenses. But so far top European scorers were well known footballers, playing in relatively decent championship. Total football was supposed to increase scoring, since it was attacking concept – instead it made scoring almost as tough as dreadful catenaccio, although the reason was different: the collective effort did not recognize designated strikers, who are fed by the rest of team and whose role is entirely and purely to provide the finishing touch, to score. Now everybody was to score – whoever get a chance. And this approach reduced the numbers practically in every country with a strong championship. The Swiss striker of FC Zurich, Peter Risi, finished third with 33 goals. It was practically accidental record for the player. Second was familiar name – the Argentine forward of Reims (France) Carlos Bianchi. He was already third scorer in Europe in 1974 – now was second with 34 goals. Steady scorer, so unlike Risi, but it was easier to score in France than in Spain or England. First with 39 goals was Sotiris Kaiafas. Who?

Kaiafas played for Omonia (Nicosia) in the lowly championship of Cyprus. The top club there, but so what? It was not like scoring plenty of goals against, say, Inter or Barcelona – it was scoring against clubs hardly anybody knew about, consisting of part-timers and amateurs. But only the total numbers counted and 39 was good deal more than 34…

On the road to the Golden Shoe – Kaiafas (high in the middle) scoring yet another goal.

Unlikely name, but the guy deserved his award under the existing rules. Sotiris Kaiafas was 27 years old, in his prime, but with almost ten years long career already. He played only for Omonia – from 1967 to 1984, a total of 388 games, in which he scored 261 goals. The numbers are impressive – a natural born goalscorer and winner. Kaifas won 9 Cypriot titles with Omonia; 6 Cups; and was 8 times top scorer of Cyprus. The championship may not have been much, but so what? Kaiafas scored 39 goals in only 26 championship games in 1975-76 – fantastic average. He is deserving legend in Cyprus and arguably the best player Cypriot player ever.

Locally – great. Objectively – hard to tell. For all his talent, Kaiafas played little for the national team – only 17 matches, in which he scored 2 goals. It is not the goals raising doubts, though – Cypriot football was very weak and the national team rarely had the chance to attack against much stronger opponents. The problem is the games played – Kaiafas had long career, yet, his caps are few. If he was the best Cypriot player, why he played rarely for the national team? And another point: better Cypriot players usually went to play in Greece – but not Kaiafas. Was he just loyal to his club and satisfied with playing at home? Or was it that even Greek clubs (so far, hardly very choosy when it came to imports) did not consider him good enough? Anyhow, Kaiafas deserves recognition just because he was fantastic scorer. He may not have been truly great player, but even in Cyprus it could not have been just sheer luck – Kaiafas had the talent, the instinct, the touch. It is not his fault the Golden Shoe deteriorated and plunged into disrepute.

Kaiafas played for Omonia (Nicosia) in the lowly championship of Cyprus. The top club there, but so what? It was not like scoring plenty of goals against, say, Inter or Barcelona – it was scoring against clubs hardly anybody knew about, consisting of part-timers and amateurs. But only the total numbers counted and 39 was good deal more than 34…

On the road to the Golden Shoe – Kaiafas (high in the middle) scoring yet another goal.

Unlikely name, but the guy deserved his award under the existing rules. Sotiris Kaiafas was 27 years old, in his prime, but with almost ten years long career already. He played only for Omonia – from 1967 to 1984, a total of 388 games, in which he scored 261 goals. The numbers are impressive – a natural born goalscorer and winner. Kaifas won 9 Cypriot titles with Omonia; 6 Cups; and was 8 times top scorer of Cyprus. The championship may not have been much, but so what? Kaiafas scored 39 goals in only 26 championship games in 1975-76 – fantastic average. He is deserving legend in Cyprus and arguably the best player Cypriot player ever.

Locally – great. Objectively – hard to tell. For all his talent, Kaiafas played little for the national team – only 17 matches, in which he scored 2 goals. It is not the goals raising doubts, though – Cypriot football was very weak and the national team rarely had the chance to attack against much stronger opponents. The problem is the games played – Kaiafas had long career, yet, his caps are few. If he was the best Cypriot player, why he played rarely for the national team? And another point: better Cypriot players usually went to play in Greece – but not Kaiafas. Was he just loyal to his club and satisfied with playing at home? Or was it that even Greek clubs (so far, hardly very choosy when it came to imports) did not consider him good enough? Anyhow, Kaiafas deserves recognition just because he was fantastic scorer. He may not have been truly great player, but even in Cyprus it could not have been just sheer luck – Kaiafas had the talent, the instinct, the touch. It is not his fault the Golden Shoe deteriorated and plunged into disrepute.

Saturday, May 26, 2012

European Player of the Year. In 1975 there was a problem and Blokhin was voted best without fully convincing observers: it was rather there was nobody truly great. 1976 vote was no better… 29 players got points, quite a big number, yet, not unusual. There were some unlikely choices, going even beyond journalistic bias and rabid patriotism – Ali Cemal of Trabzonspor (Turkey) got a point. The Swedish player of Tennis Borussia (West Germany), Benny Wendt, got 2 points. Well, Trabzonspor at least were champions of Turkey - Tennis Borussia played Second Division! Wendt probably deserves mentioning just because he is the only second division player to appear in so prestigious award. How good were these two guys? Pause and think hard… and find nothing. Wendt hardly ranks high in Swedish football history, let alone German one. On the other hand there were significant absences: the whole British football failed – only Kevin Keegan got points. The Italians faired just as bad. Spanish too. Even the champions of Europe – Czechoslovakia – did not go very high. Individually, Johan Crujff dropped to 7th place with measly 12 points. It was shared with the Yugoslavian goalkeeper of St. Etienne Ivan Curkovic, a very consistent and solid player, but hardly a superstar. Oh, well, Crujff was entangled in a fight with his coach and had weak season, but… he ended 10 points above Benny Wendt and almost 80 points behind the winner. Numbers tell something… names too. Only two young and coming players appeared in the top 5 – Michel Platini (AS Nancy) was 5th and Kevin Keegan (Liverpool) – 4th. Both were far behind the third placed Ivo Viktor. The goalkeeper of the new European champions was neither young, not unknown – and so far was never ranked among the best goalkeepers, let alone the top players of the continent. Was he suddenly improved? Or was his club Dukla (Prague) making the news? Not at all. Viktor got points largely because of the European title and may be because of seniority – some of his teammates were more impressive than him, yet, not overwhelmingly impressive. Rob Rensenbrink ended on second place – a big star since 1974 the Dutch was hardly better in 1976 than in 1974… like Viktor, he most likely ranked so high because of the success of Anderlecht this year. But Rensenbrink did not come even close to the winner with his 75 points: the best one finished with 91. Numbers tell and numbers lie… the difference appear very impressive. The name of the winner no less… Franz Beckenbauer.

A name so familiar, there is no need to add words. A face so familiar, it is very difficult to find lesser known – not really rare – photo. And here he is on the left with his equally familiar, ‘eternal’, surrounding: Maier and Schwarzenbeck. This is 1975 and Maier receives an award, but when it came to mega-awards – the Kaiser got them. Third time European Player of the Year! His rivalry with Crujff remained open – they were tied once again. No doubt, Beckenbauer is one of the greatest all-time footballers, but was really that strong in 1976? Remember, most of the time individual awards follow club success. Bayerm won the European Champions Cup and the Intercontinental Cup. Lost the European Supercup and had the worst Bundesliga year to date. West Germany reached the European final, but lost the title to Czechoslovakia. Not really great year… and Beckenbauer was aging. A player of his caliber hardly drops to really weak performance, but decline was noticeable: if anything, Beckenbauer was not better than few years back. His win was due to reputation, combined with something more sinister: European football was changing. Total football, as flashy as it was originally, emphasized collective effort. It was no longer a matter of individual greatness – and the results of it were obvious: there were no longer really great individual stars. Not in Czechoslovakia, not in Bayern, not in Anderlecht. The best players were getting relatively equal – team work took away the luster. Lack of real individual greatness affected voting the best individual for a second year already - the winners were not all that exciting. But who else? Benny Wendt? Looks like the journalists voted conservatively for the familiar reputation. Good for Beckenbauer, of course, but there was bitter aftertaste.

A name so familiar, there is no need to add words. A face so familiar, it is very difficult to find lesser known – not really rare – photo. And here he is on the left with his equally familiar, ‘eternal’, surrounding: Maier and Schwarzenbeck. This is 1975 and Maier receives an award, but when it came to mega-awards – the Kaiser got them. Third time European Player of the Year! His rivalry with Crujff remained open – they were tied once again. No doubt, Beckenbauer is one of the greatest all-time footballers, but was really that strong in 1976? Remember, most of the time individual awards follow club success. Bayerm won the European Champions Cup and the Intercontinental Cup. Lost the European Supercup and had the worst Bundesliga year to date. West Germany reached the European final, but lost the title to Czechoslovakia. Not really great year… and Beckenbauer was aging. A player of his caliber hardly drops to really weak performance, but decline was noticeable: if anything, Beckenbauer was not better than few years back. His win was due to reputation, combined with something more sinister: European football was changing. Total football, as flashy as it was originally, emphasized collective effort. It was no longer a matter of individual greatness – and the results of it were obvious: there were no longer really great individual stars. Not in Czechoslovakia, not in Bayern, not in Anderlecht. The best players were getting relatively equal – team work took away the luster. Lack of real individual greatness affected voting the best individual for a second year already - the winners were not all that exciting. But who else? Benny Wendt? Looks like the journalists voted conservatively for the familiar reputation. Good for Beckenbauer, of course, but there was bitter aftertaste.

Wednesday, May 23, 2012

South America went Brazilian – as far as club representation was concerned. Awarding went against the ‘rules’ too – the Libertadores Cup finalists had no players among the top three. Rivelino, playing for Fluminense by now, got the third place. Zico of Flamengo was second. It looked like Flu-Fla derby once again, but since neither club won anything, something else was more interesting. The overall South American football was still lagging behind the Europeans. There was nothing really new and Brazilian skill and artistry got the upper hand, but it was a bit strange. Rivelino was great player – no doubt about it – but by 1976 he was no longer improving. He was getting older, obviously reached his peak a few years back, and his presence represented lack of new exciting legs. One thing was certain: at the end of the 1960s Rivelino was seen as possible ‘new Pele’ – the player was denying that, arguing the uniqueness of the King, but expectations were impossible to suppress. By 1976 it was well clear that he never came even close to Pele and was not going to become better. Zico – ‘the White Pele’ – finally got recognition, partial one, as it was, but after 6 years of professional football he was still considered ‘promising youngster’. Pele was national team regular before he was 20 – Zico hardly ever played for Brazil yet. Most importantly, no matter how good Rivelino and Zico were, their clubs failed to win the Brazilian championship. Both Flamengo and Fluminense were not the leading clubs at home – so unlike Pele’s Santos of the early 1960s.

South American Player of the Year was voted Elias Figueroa. The Chilean defender was champion with Internacional (Porto Alegre), ranked very high in Brazilian football, and was probably the closest thing to the modern European ‘libero’ South America had at the time. Figueroa was ranked the best South American for a third time in a row – enourmous achievement by any standard, especially given the continental preference of flashy strikers.

How great is great? If one is voted continental best three times in three years, there should be no doubt about quality. In South America Figueroa became a legend. He was voted also FIFA’s player of the year – the best in the world, that is. Yet… outside South America he continued to be relatively unknown. Probably the most unapreciated player of the 1970s. Hats down to him, though.

Monday, May 21, 2012

And after the best clubs – the best individuals. There is pattern in the election of best players of the year: usually the best player belongs to highly successful club. Yes, it seems logical – the best clubs are made of best players – but it is also inertia. Just because a team is winning does not mean automatically that the best individual footballer plays there. But winning counts most… Thus, the voting for African Player of the Year reflects the success of the clubs – Ali Bencheikh of MC Alger was third. Second was Papa Camara (Guinea) of the African Champion Cup’s finalist Hafia (Conakry). Best of all was player, who does not need an introduction today. Back in 1976 he was not exactly a newcomer either – was second placed in 1975 – but his name meant absolutely nothing. Some Cameroonian called Roger Milla.

Photos of his first glory are widely unavailable… Milla was 24 years old and played for Tonnere (Yaounde), one of the best Cameroonian clubs at the time, but the football of the country were still rather weak in Africa, not to mention the world. Hence, unknown… As for Milla, he was born in the country’s capital Yaounde, but started his playing career in the other big football city of Cameroon, Douala. According to available data, he debuted way back – in 1965 – for Elcair (Douala). African statistics, when existing at all, are notoriously unreliable, so info has to be taken with a grain of salt: in 1965 Milla was 13-years old. Suspiciously young, if data concerns men team, as it looks like. But it is possible… after all, the best clubs in the world are often founded by schoolkids, who made the squad in the early days. Amateur football even today includes teenagers in nominally men’s squads. African football was both young and amateur in 1976, and even more so in 1965… Milla’s early days may be true. Or not. Who can really check and prove beyond doubt? Anyhow, the record tells that Milla played 61 games and scored 6 goals for Elcair until 1971. Then he moved to bigger and better club – Leopard (Douala). For them he played 117 matches, scoring impressive 89 goals in three years. And in 1974 Milla either got homesick or his talent tempted the finest Cameroonian clubs, for he finally returnedto Yaounde and joined Tonnere. It was steady upward development, eventually noticed abroad and awarded – second in Africa the year before and the best player of the year in 1976.

Yet, it is difficult to assess the qualities of Milla. Although France Football magazine organized the vote, European based professional African players rarely appeared in the list. Was Milla really better than those playing in Europe? This is big ‘may be’ – against Milla go two things: the best African player triggered no interest in Europe. Nobody rushed to offer him a contract until 1977, and the offer came from a small club, Vallencienes (France). Even if the Europeans were jaded and racists, there was something close to home: Milla not only did not play a single match for Cameroonian national team, but his continental fame did not lead to invitation. His debut for Cameroon came in 1978, when he already played in France. So how great he was? I am not certain – at the time there was much better known Cameroonian player: Manga-Oungene, who never made it to Europe, but was thought perhaps the brightest African player. But in those days African players got little exposure anyway: from the top three only Milla and Bencheikh appeared at World Cup finals.

But Roger Milla was to get real fame eventually. Sure, he had to wait many, many years for that, until his goals, his dance, and his age made him world famous.

Can’t mistake this grin? Back in 1976 Milla himself would not believe that he will be Coca-Cola poster boy one day. Well, a grandpa, rather than a boy… fame came late to him, although his first big award was achieved when he was only 24.

Photos of his first glory are widely unavailable… Milla was 24 years old and played for Tonnere (Yaounde), one of the best Cameroonian clubs at the time, but the football of the country were still rather weak in Africa, not to mention the world. Hence, unknown… As for Milla, he was born in the country’s capital Yaounde, but started his playing career in the other big football city of Cameroon, Douala. According to available data, he debuted way back – in 1965 – for Elcair (Douala). African statistics, when existing at all, are notoriously unreliable, so info has to be taken with a grain of salt: in 1965 Milla was 13-years old. Suspiciously young, if data concerns men team, as it looks like. But it is possible… after all, the best clubs in the world are often founded by schoolkids, who made the squad in the early days. Amateur football even today includes teenagers in nominally men’s squads. African football was both young and amateur in 1976, and even more so in 1965… Milla’s early days may be true. Or not. Who can really check and prove beyond doubt? Anyhow, the record tells that Milla played 61 games and scored 6 goals for Elcair until 1971. Then he moved to bigger and better club – Leopard (Douala). For them he played 117 matches, scoring impressive 89 goals in three years. And in 1974 Milla either got homesick or his talent tempted the finest Cameroonian clubs, for he finally returnedto Yaounde and joined Tonnere. It was steady upward development, eventually noticed abroad and awarded – second in Africa the year before and the best player of the year in 1976.

Yet, it is difficult to assess the qualities of Milla. Although France Football magazine organized the vote, European based professional African players rarely appeared in the list. Was Milla really better than those playing in Europe? This is big ‘may be’ – against Milla go two things: the best African player triggered no interest in Europe. Nobody rushed to offer him a contract until 1977, and the offer came from a small club, Vallencienes (France). Even if the Europeans were jaded and racists, there was something close to home: Milla not only did not play a single match for Cameroonian national team, but his continental fame did not lead to invitation. His debut for Cameroon came in 1978, when he already played in France. So how great he was? I am not certain – at the time there was much better known Cameroonian player: Manga-Oungene, who never made it to Europe, but was thought perhaps the brightest African player. But in those days African players got little exposure anyway: from the top three only Milla and Bencheikh appeared at World Cup finals.

But Roger Milla was to get real fame eventually. Sure, he had to wait many, many years for that, until his goals, his dance, and his age made him world famous.

Can’t mistake this grin? Back in 1976 Milla himself would not believe that he will be Coca-Cola poster boy one day. Well, a grandpa, rather than a boy… fame came late to him, although his first big award was achieved when he was only 24.

Saturday, May 19, 2012

If North American football was well moneyed construct, aiming to become a miracle, African football was poor, but real miracle. It was miracle, because the continent lacked resources in every aspect – from stadiums to skills and from organization to transportation. It seemed fueled entirely by enthusiasm and no matter what kind of objective and subjective difficulties the game was facing, it was popular and international tournaments run their course. Under abysmal conditions, the African Champions Cup was staged with amazing regularity. The schedules were complicated, but eventually better teams moved ahead and reached the final stage. In 1976 the finalists represented the great African divide: old, better organized Arab football vs Black African talent, coming out of nowhere. Hafia (Conakry, Guinea) and Mouloudia Club d’Alger (Alger, Algeria). Hafia was ambitious to make a double – they won the African Champions Cup in 1975 and the first home leg of the final they them very solid lead – 3-0.

Anywhere else the first macth result would have been decisive – but Africa was unpredictable and no first match result was a guarantee.

Hafia found themselves largely defending and not very successful at that – the Algerians scored three goals and at the final whistle it was a 3-3 tie from both legs.

The final went into penalty shoot-out and the hosts were supreme. However, what was the result? An internet site dedicated to MC Alger and providing plenty of information about the final omits the shoot-out entirely. Other sources are contradictive: some give 3-0 MC Alger; others 4-1; and sometime both results are given in the same source. One thing is certain – MC Alger gained a decisive lead by three goals and collected the Cup. It was their first African Champions Cup and players, functionaries, fans were jubilant. Rightly so.

Anywhere else the first macth result would have been decisive – but Africa was unpredictable and no first match result was a guarantee.

Hafia getting ready to win second African trophy in Algeria. They appeared to be favourites and eager to fight.

But it was not to be their night – at home, MC Alger attacked relentlessly, cheered by crowds of supporters.

Hafia found themselves largely defending and not very successful at that – the Algerians scored three goals and at the final whistle it was a 3-3 tie from both legs.

The final went into penalty shoot-out and the hosts were supreme. However, what was the result? An internet site dedicated to MC Alger and providing plenty of information about the final omits the shoot-out entirely. Other sources are contradictive: some give 3-0 MC Alger; others 4-1; and sometime both results are given in the same source. One thing is certain – MC Alger gained a decisive lead by three goals and collected the Cup. It was their first African Champions Cup and players, functionaries, fans were jubilant. Rightly so.

Mouloudia, or MC Alger, or MCA were old club by African standards – found in 1921. They were traditionally strong in Algeria, and also very popular: the club is considered, may be rightly, the most popular Algerian club, and – more questionable claim – one of the most popular on the whole continent. At last international success was added to popularity.

Here are the conquerors, who may be count for more than just Algerian success: it was victory of Arab football, of the older and better developed game from the African North, after years of Southern victories. The team itself is virtually unknown outside Algeria.

The captain Bachi got some attention in France, practically the only country covering African football in Europe – Mirroir de Football called him ‘the architect’ of MC Alger, which makes him the team’s playmaker. How classy he really was remains unknown, for Bachi apparently was not hunted by European clubs. But he was great in Africa this year and certainly is MC Alger’s legend.

Wednesday, May 16, 2012

The world was hearing more and more about NASL – a mixed US-Canadian league, which, however, was understood mostly as US-league, for Canadian news were few – the big hype was South of the border. Outside North America it was not the quality of the game – abysmal, by all accounts – but the hype of the signing. At home, that was the strategy anyway: sign big names, make a lot of publicity about it, and may be the general public will swallow the new sport. The competition was stiff, of course, and curiously NASL brains took the approach of selling a show rather than really competitive sport. The ‘biggest stars’ of the world played in NASL – go and see them! The Americans went without having a clue about the sport – they still don’t. Pouring money was seen as the panacea – lucrative players’ contracts, massive advertisement, but cheap tickets, often family packages. People went for cheap entertainment – games were amazingly well attended – but the clubs were losing money all the time. Big spending would elevate the sport, was the wisdom. The ills of the concept are well documented, but still a few words: organizers had no idea what is to build a team. They may not have been familiar with football, but were more than familiar with other American sports – and that is what makes their practices so weird. Evidently, they thought it was enough to import a whole line of players from some foreign club and – presto, you get a running team. There was a team almost entirely made of Mexicans. Pele did not come alone, but with two more Santos players: the Peruvian star Ramon Mifflin and the Brazilian Nelsi Morais. British players were brought by the carload… In later years, when the failure of NASL was contemplated, it was said that ignorance played a big role and the league was flocked by mediocrities of foreign origins. ‘Everybody was saying he was a Polish national team player’, mused one former NASL suit, but this was not entirely true – in fact, NASL was largely British. It was crazy picture – aging stars, young hopefuls, mid-aged journeymen, drunks, players on loan, ‘guest’ players, players on vacation, injured, healthy, you name it… it was something like paid vacation and no doubt everybody getting their chunk remembers fondly ‘the days’. It was truly days sometime: many players came just for the summer, between European seasons. Many were registered as active players both in USA-Canada and at their more serious home clubs in Europe. A lot played only a game or two as ‘guest appearances’. No league in the world was organized in such careless way, but money were great no matter what was delivered. Future was not exactly considered – it was only for the moment, for ‘now’. No other North American sport operated in such way – teams were built normally there, for years and aiming at making of strong and long-lasting competitive teams. Football was a circus, topped by ‘international’ games like USA-Italy, where the visitors, lured to come for ‘official’ match, faced a squad of foreigners, Pele included. No wonder FIFA grumbled and threatened to outlaw NASL: basic rules were constantly disregarded.

No wonder foreign players were attracted to NASL – effortless cash. It was never a news, but Horst Koeppel played for Vancouver Whitecaps in the summer of 1976. Yes, he was a member of the great Borussia (Moenchengladbach) squad at the time and played serious football in the Bundesliga. And just because of that, it was unlikely that he put much of an effort in Vancouver: why risking injury or getting tired? Bundesliga league season was soon to begin, and that mattered – not NASL. No wonder nobody remember him in North America and his stay in Vancouver is more than dubious – what kind of contribution can make a player, hired for a few weeks? Certainly it had nothing to do with team building.

To which the American transfer policies contributed gravely as well: they were so loose, a player often appeared in few clubs in a singular season. Eusebio was like that, for instance – including a brief return to Portugal, where he still managed to play 12 matches for Beira Mar before the year ended.

Dreams coming true… Chinaglia and Pele. So many players dreamed to play along with the King, but for Chinaglia it became reality.

Well, Cosmos looked like sure champions with this squad.

Here are the champions. One player was seemingly enough to win the championship – it looks like so, for the rest are entirely unknown. As the name suggests, the Canadian club had ethnic origins, well preserved in the making of the squad. The mystery, however, is who was Canadian player, even by naturalization, and who was foreign import: most players are clearly ethnic Croatians, but since not a single name rings any bell, they were recruited from the Croatian community in Toronto; not imported from Yugoslavia. The German Wolfgang Suhnholz was also likely naturalized Canadian and not Bundesliga import. Kapetanovic was voted NASL coach of the year, but he too seems naturalized Canadian. Most likely only Eusebio and Evair were ‘true’ imports. It looks like better work was done in Toronto than in New York and elsewhere: the squad is not rag-tag collection of player, but more carefully build from local guys. It was a team, to which Eusebio (who did not stay with Metros-Croatia after winning the title) added class and experience. The winners confirmed old truism: names do not win; teams do. Unfortunately, the increasing importation of foreigners by other clubs left no chance for these guys to repeat their success: they were really small fry. The policies of NASL discouraged team building and perhaps this was the biggest reason for collapse of the league: why trying to teach some Grnja play decent football if you can get Beckenbauer? Oh, well, New York Cosmos had to sulk in 1976 and Eusebio added one more title to his collection.

The season ended optimistically, though. Big names were gathering in the league, Pele mingled with the famous businessmen, rock and film stars, NASL looked stable with 20 clubs second year in row. May be the next year NASl will edge at least ice-hockey and become the forth important American sport? Ah, skies were the limit… booze was limitless for Bestie.

But the hype was growing and NASL, if anything, was pouring more fuel. In 1975 Pele was signed and that was news made so big, other transfers were practically ignored – Eusebio and his Benfica and Portugal teammate Antonio Simoes also came to NASL in 1975. 1976 really opened the gates: George Best, Bobby Moore, Rodney Marsh arrived, to mention only the biggest names. They were all Fulham players – and remained so: in fact, they played for two clubs simultaneously (well, registered in two clubs in reality – probably the formal situation was described as ‘loan’).

George Best playing for Los Angeles Aztecs. He loved USA and stayed in NASL for years. For him, it was easy, anonymous, and relaxing life, dedicate to the bottle. His drinking buddies from Fulham – Marsh and Moore – faired well in NASL too… It was fun:

NASL loved and encouraged ‘reunion’ photos, like this friendly chat between Pele and Simoes, but a picture like this not only represents the relaxed North American football, but also questions strongly the true nature of the American brand. Was it serious at all? For anybody? In seriously competitive leagues players of opposite teams are never seen friendly together before the game or immediately after the final whistle.

Stars are stars, but overall the league was mediocre…

Pele vs Jose Soroa. Soroa was Uruguayan, but who was he? No wonder, old Pele still shined.

To which the American transfer policies contributed gravely as well: they were so loose, a player often appeared in few clubs in a singular season. Eusebio was like that, for instance – including a brief return to Portugal, where he still managed to play 12 matches for Beira Mar before the year ended.

Yet, with all media hype, North American football remained largely unknown: New York Cosmos was the only familiar club, thanks to the transfer of Pele. Of course, Cosmos was spending most money and even more in the future, when they seriously got all the big names of the 1970s, but Pele propelled them to fame outside North America.

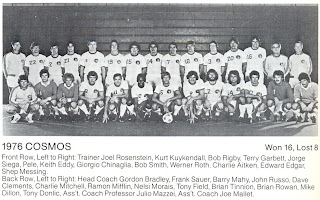

Here they are in 1976. Having already Pele, Mifflin, and Nelsi Morais, Cosmos made new move – and quite unusual one too: they acquired the services of actual star, not some famous name on his last legs. Giorgio Chinaglia was bought from Lazio. Chinaglia was fed up with hostility in Italy; money were great, he moved. He was 29 years old, not exactly young, but still in his prime. Very likely not Pele, but Chinaglia was the greatest star of Cosmos – he played in New York for many years, and inspired his teammates no matter how famous, or anonymous. He contributed a lot: he arrived with a bang, becoming the top goalscorer of the 1976 NASL season.

Dreams coming true… Chinaglia and Pele. So many players dreamed to play along with the King, but for Chinaglia it became reality.

Well, Cosmos looked like sure champions with this squad.

They were not. The King of the world lost to the former King of European football.

Eusebio in attack, with teammate Wolfgang Suhnholz and Kick’s defender Sam Beck around. NASL teams sported weird kits as a rule, but Eusebio here is equipped with true to the sport and fashionable Adidas. No, it is not Benfica, but his current club Toronto Metros-Croatia. His arrival to North America in 1975 was almost anonymous, because of the noise Pele’s transfer made. But Eusebio won the NASL title in 1976 and Pele did not…

Here are the champions. One player was seemingly enough to win the championship – it looks like so, for the rest are entirely unknown. As the name suggests, the Canadian club had ethnic origins, well preserved in the making of the squad. The mystery, however, is who was Canadian player, even by naturalization, and who was foreign import: most players are clearly ethnic Croatians, but since not a single name rings any bell, they were recruited from the Croatian community in Toronto; not imported from Yugoslavia. The German Wolfgang Suhnholz was also likely naturalized Canadian and not Bundesliga import. Kapetanovic was voted NASL coach of the year, but he too seems naturalized Canadian. Most likely only Eusebio and Evair were ‘true’ imports. It looks like better work was done in Toronto than in New York and elsewhere: the squad is not rag-tag collection of player, but more carefully build from local guys. It was a team, to which Eusebio (who did not stay with Metros-Croatia after winning the title) added class and experience. The winners confirmed old truism: names do not win; teams do. Unfortunately, the increasing importation of foreigners by other clubs left no chance for these guys to repeat their success: they were really small fry. The policies of NASL discouraged team building and perhaps this was the biggest reason for collapse of the league: why trying to teach some Grnja play decent football if you can get Beckenbauer? Oh, well, New York Cosmos had to sulk in 1976 and Eusebio added one more title to his collection.

Monday, May 14, 2012

And after South America there is, as always, little left of the world. Mexico, never attracting much attention, was further dwarfed by NASL in terms of coverage. Regular championships continued, foreign players were imported from South America, but the better known names rarely came to play in Mexico and local players were going to play in USA as well. Out of sight, quietly, football concerned local public only. America (Mexico City) won the championship.

Who were the champions is hard to tell, but their fans surely were happy. The team had some South Americans who obviously helped and city rivals like Cruz Azul, Necaxa, UNAM ate dust. America’s victory was lost to the world, though.

One of the big Mexican clubs, they were historically not big winners, but popular and usually performing well.

Who were the champions is hard to tell, but their fans surely were happy. The team had some South Americans who obviously helped and city rivals like Cruz Azul, Necaxa, UNAM ate dust. America’s victory was lost to the world, though.

Saturday, May 12, 2012

And finally scraping the bottom – Venezuela. The pariahs of South American football: nobody even noticed them, but football was played professionally there too. Just a glimpse is possible – not of the champions, Portuguesa FC, but of another club, which is fairly succefull in the Venezuelan championships.

Deportivo Galicia. Looking sharp, yet, entirely unknown. Only one thing could be said – apparently, Venezuela attracted foreign players – two Uruguayans, an Argentine, and a Spaniard here. Small fry, but for these guys Venezuelan wages were obviously preferable to those at home. The other thing worth mentioning is again Professor de Leon – he is highly respected there and considered one of the biggest influences in the history of Venezuelan football.

But Venezuela is unique: the only South American country where football is not the most popular sport: baseball is. Hmmm, Yankees interested in oil for a long, long time… and introducing their own sport to the masses as well.

Deportivo Galicia. Looking sharp, yet, entirely unknown. Only one thing could be said – apparently, Venezuela attracted foreign players – two Uruguayans, an Argentine, and a Spaniard here. Small fry, but for these guys Venezuelan wages were obviously preferable to those at home. The other thing worth mentioning is again Professor de Leon – he is highly respected there and considered one of the biggest influences in the history of Venezuelan football.

But Venezuela is unique: the only South American country where football is not the most popular sport: baseball is. Hmmm, Yankees interested in oil for a long, long time… and introducing their own sport to the masses as well.

Wednesday, May 9, 2012

Colombia was off the radar for a long time. Well, it produced and peddled cocaine back then just like now and the drug cartels run Colombian life, and Leftist guerillas striked from the jungle, and so on – but hardly anything caught the media interest. Football was not news either, although judging by the champions, drug lords liked football. Long gone were the glorious years of the Colombian illegal championship, studded with world-class stars and outside South America practically nothing was known about the Colombian game. The best known to outsiders club – Millonarios (Bogota) – was matched by other clubs and not at all dominant. Generally, three cities shaped the local scene – Cali, Medellin, and Bogota, increasingly failing to third place in importance. The championship format was changed in 1968 to the complicated and strange structure, favoured in South America – two separate championships in a single year, Apertura and Clausure, followed by play-off final championship. Deportivo Cali were runners-up in 1976, but champions were Atletico Nacional (Medellin). Drug money come to mind at once… it was Atletico Nacional’s third title so far – they were already champions in 1954 and 1973.

Forget the drug cartels – this is green and white pride: top, from left: Eduardo Retat, Iván Darío Castañeda, Gerardo Moncada, Miguel Angel López, Francisco Maturana, Jorge Olmedo.

First row: Jorge Peláez, Gilberto “Comanche” Salgado, Ramón César Bóveda, Eduardo Emilio Vilarete, Raúl Ramón Navarro

Even with Comanche in the team, hardly known to anybody… but there was a guy, who is world famous today: one Francisco Maturana. Nobody knew the player, but the coach was another matter. Among other things, Maturana always speaks of the importance of Uruguayan coach Professor de Leon (see earlier posting on Uruguay). As far as 1976 is concerned, Maturana was champion player. Not bad.

Monday, May 7, 2012

It was really a year of surprises, shaking traditional establishment – new champions in Uruguay, in Peru, and Chlie did not lag behind. The bottom of the table shuffled familiar names: Rangers (Tacna), Naval (Talcahuano), and Deprotes La Serena (La Serena) were relegated to seond division; Nublense (Chillan), O’Higgins (Rancagua), and Audax Italiano (Santiago) were promoted to first. The whole group of teams changing leagues was interesting: all of them were primarily top league clubs, some quite successful in the past. The very fact that such clubs were playing, even occasionally, second division football suggests major changes occurring. The military dictatorship was probably direct and indirect reason: reshaping of Chilean football started as soon as General Pinochet’s junta took the power in the country. Political pressure perhaps declined some clubs, but there were economic results – unlike the rest of Soith American military rulers, the Chilean military was economically effective and economic improvement led to the rise of unlikely provincial clubs from industrial towns – Cobreloa and Cobrasal are the prime examples. Yet, this was to become really a few years later – so far, the more likelier case was the decline of leaning to the Left clubs: Colo-Colo suddenly was not so great as traditionally it was. There was already a champion, who never won anything before, so the changes in Chilean football started earlier than those in Uruguay and Peru. They started, but they hardly positive – it was more a case of using the vacuum left after traditional powers declined for whatever reason. And the nickname of the 1976 champions jokingly suggests precisely that: ‘Ruleteros’ (the Roulette players, the gamblers) won. That is Everton (Vina del Mar).

The name clearly indicates origins: back in 1909 a group Anglo-Chilean teenagers dreaming football at the Chilean Pacific coast organized their own club and named it after the club supported by their very English fathers. In theory, the Liverpudian derby can be fully recreated in South America: only Everton has to travel to the Atlantic coast and to another country, to challenge Liverpool (Montevideo). In reality, they had to settle for more immediate rivals, which in Chile, like everywhere in South America, often have English names. Everton’s derby developed with their neigbours: Santiago Wanderers (Valparaiso). It represents bitter rivalry between old and poor city, Valparaiso, vs rich and glamorous one, Vina del Mar. But that is local – on larger scale, Everton were just one more provincial club dwarfed by the ‘grands’ from the capital.

But Everton were special – they won 2 Chilean championships in 1950 and 1952, becoming the most successful provincial club in Chile and very likely in the whole South America. Their victories were ancient history by 1976, so the Chilean championship mirrored Peru and Uruguay this year. Everton played well enough, but ended with equal points with Union Espanola (Santiago). Just like in Peru, final play-off was scheduled to decide the new champions. Again like Peru, the final opposed smaller, yet, traditionally stronger than provincial clubs, team from the metropolitan (Callao is separate city, but really merged with Lima) to true provincials. Unlike Peru, but like the Uruguayan Liverpool, the intruders were old club, alaways in the shadows of bigger rivals. In Chile, like Peru and Uruguay, small clubs and particularly provincial ones excited largely for variety. But not this year: the first final ended in a 0-0 tie and second one was played, which Eveton won 3-1 and grabbed their third title.

Union Espanola – fighting to the end, but failing. Clubs from capital cities were doomed to failure in 1976.

Champions after almost quarter of a century. Second row, from left: Humberto Lopez, Angel Brunell, Erasmo Zuñiga, Julio Nuñez, Guillermo Azocar, Leopoldo Vallejos. Bottom: Sergio Gonzalez, Guillermo Martinez, Jorge Spedaletti, Mario Salinas, Jose Luis Ceballos.

Vina del Mar may have reputation for glamour and sophistication, but these boys a pretty much a cliché of Latin Americans with so many moustaches. No doubt, their long hairs helped winning the title.

The real strength of the team is hard to evaluate. Mario Galindo, Julio Nunez, Humberto Lopez, Leopoldo Vallejos, Carlos Caceres, Mario Salinas, Jose Luis Ceballos… surely legends in Vina del mar, but unknown outside Chile. Sergio Ahumada was the only known name, providing class. Ahumada is perhaps unique player – wherever he went, he won a championship, and he frequently moved from club to club. Despite their origins, there was not a single player with English name in Everton.

By itself, glorious season for Everton, but there was something more – they contributed to the reshuffling of South American football. Smaller and provincial clubs were rising and breaking old hegemonies in Peru, Chile, Uruguay. 1976 is significant for that long lasting change. The new champions may have been accidental, but their example was to be followed by others.

Saturday, May 5, 2012

Peru more or less ranks fifth in South America, but let move them one place up the scale: Peru won the 1975 South American championship. A cluster of stars made the Peru successful since 1969, but what was behind Cubillas, Sotil, and Chumpitaz? Well, Peruvian clubs played quite well in Libertadores, although not exactly contenders. To the world, Peruvian domestic football was largely unknown. In the Andes the game suffered the universal South American problems: lack of money, exodus of star players, outdated tactics, old stadiums, and tendency of concentration in one-two big cities. In 1973 the Peruvian federation decided to enlarge the first division in order of having more provincial clubs at top level. Very likely the real idea was to help the big Lima clubs, rather than the official line of helping development of national football: big clubs playing at provincial towns normally increase attendance, hence, the revenue. However, in South America this is more of a wishful thinking for resolving chronic financial troubles: travel was expensive and difficult, and going to the provinces hardly ever brought money to suffering clubs. National federations have forever to maneuver between the demands of the big clubs and the pressure of the many provincial clubs, who feel under-represenation and administrative suffocation. Anyway, Peru increased the top league from 18 to 22 clubs for the 1974 season, and 6 teams were promoted in 1973 to fill the new spots plus the two vacated ones by relegated teams. Union Huaral was among the newly promoted – it was sheer luck, for they were did not end first or second, the normal promotion spots at the final table. After the increase, the league was reduced – to 16 clubs in 1976 – but the new boys managed to escape relegation. Escape? There was no escape – Union felt at home in First Division. More than at home: they won the championship! Actually, it was not easy victory - the provincials were tied up with Sport Boys (Callao) at the end of the season and final championship play-off was scheduled. This match Union won 2-0 and took the trophy to Huaral.

‘Naranjeros’ are relatively young club – founded in 1947, which is years after the ‘grand’ Peruvian clubs were established. New clubs very rarely have big impact in countries with old football clubs, and for years Union Huaral played the expected role – small, insignificant provincial club. Usually such clubs have occasional success only in difficult times, when the big traditional powers suffer major economic decline. To a point, it was the case in 1976, which makes it difficult to really figure how good were the champions. Just like in Uruguay, it appeared to be a lucky occasion, largely due to big clubs weaknesses. And similarly to Uruguay, although not on the same scale of importance, the year was historic in Peruvian football: the chance given to provincial clubs proved worthy, they were competitive enough, and the young club from Huaral won their very first title, breaking the tradition.

Brave new champions: top, from left: Carlos Campaña, Eusebio Acazuso, Hipólito Estrada, Walter Escobar, César Cáceres y Luis Pau.

Bottom: Mario Gutiérrez, Pedro Ruíz, Víctor Espinoza, Alejandro Luces y Eduardo Rey Muñoz.

No famous players here, so it is impossible for an outsider to estimate the strength of the team. Most likely, the boys were relatively equal to most Peruvian teams, and enthusiasm propelled them to final victory. The club was not to become major force in Peruvian football, but rather mid-table first division team. Even if only that, it was great – they managed to establish themselves among the top Peruvian clubs. For young provincial club – well done. Peruvian football history added one more name to the list of champions.

Wednesday, May 2, 2012

On the Northern shore of La Plata military dictatorship was already old news and football hit perhaps its bottom. Nothing was left of once upon a time great Uruguayan football, except constant exodus of players, going everywhere – from Greece to Venezuela. Some were returning home too, but not in great numbers. Yet, 1976 was historically significant year and not for one, but for two important reasons. The first was immediate; the second is still not fully recognized. Uruguayan football was practically Montevideo football – the 22 teams playing in First and Second Division were all from the city – and this remained unchanged: La Luz won promotion from Third Division, preserving the status quo. Up the scale there was no option at all – Fenix was relegated from First, although they finished 9th in the 12-club league (complicated system, taking at least two seasons accumulated record to decide the club moving down) and replaced by inevitable other Montevideo club: Bella Vista. So far, nothing new.

The real bomb dropped among the best: Defensor took the championship.

‘Violeta’ were not some newcomers – the club was founded in 1913, originally as Club Atletico Defensor. Today the name is slightly different: Defensor Sporting Club, but was always known simply as ‘Defensor’. Until 1976 they won plain nothing, but their first ever title had bigger significance: it was the first other than Nacional and Penarol club to win the championship since 1931. That was the last amateur season, so Defensor were the third ever club winning the professional championship. Breaking the duopoly was exciting, yet, considering the grave state of Uruguayan football, the surprise was taken a bit skeptically: the weakness of the big clubs rather the strength of Violeta may have been the reason… a freak accident. However, 1976 marked the end of duopoly – nobody knew it back then, but the duopoly was finished for good. As for Defensor – well, first title is always fantastic for club and fans.

Historic champions: top, only players,from left: Freddy Clavijo,Baudilio Jauregui, Ricardo Meroni, Ricardo Ortiz, Behetoven Javier, Liber Ariste.

Bottom: Luis Cubilla, Jose Gervasio Gomez, Alberto Santelli, Rodolfo Rodriguez, Pedro Graffigna.

For champions, especially judged by outsiders, Violeto did not look impressive – except experienced national team defender Jauregui, the named were unknown. Before the season a bunch players departed to play abroad, eventually followed by Jauregui as well, who moved to Argentina and Union (Santa Fe). But the club acquired the services of Luis Cubilla, perhaps the greatest Uruguayan player of the 1960s. By now Cubilla was 36 years old, returning from a spell with Santiago Morning (Chile). The transfer was a classic – smaller football clubs recruit famous veterans, hoping they would help both performance and gates. And often veterans really help and teams improve, however, one or two players on their last legs are never enough to win championships. Cubilla added his signature posture to team photos – semi-crouching, facing the lenses with his profile, always at the end of first row – and his experience, but was helping the miracle, not making it. The real miracle-maker was somebody else – the coach.

Professor Jose Ricardo de Leon was and is virtually unknown outside South America, but was already almost legendary there. A former player and real professor of physical education, he alternated coaching and academic work. In 1975 he made Toluca champion of Mexico, then spent the second half of the year in Argentina, coaching Rosario Central with Kempes, and returned home to take the reigns of Defensor at the beginning of 1976. Very likely Cubilla was persuaded to play for Defensor by Prof. de Leon (he is always mentioned as ‘Professor de Leon’ by the formal and conservative Uruguayans), but the coach really assembled a squad of young players – some who played at the South American Juniors championship in 1975, and others who did not: Ortiz, Washington Gonzalez, Clavijo, Conde, Caceres, Rudy and Rodolfo Rodriguez, Graffigna. On the surface, it looked like the coach depended on mixture of youth enthusiasm, added by the authority and experience of Cubilla, but it was much more than that – Prof. de Leon had a particular tactical vision in mind and made a team to serve it. His system was radically innovative: 4-2-3-1. Evidently, it was successful, but also universally disliked. Critics grumbled against it – it was ultra-defensive. Since total football was the way, and South Americans lagged behind Europe in adapting it, to introduce defensive tactics was not even reactionary: it looked rather hopeless. However…consider this: most of the teams at the 2010 World Cup played exactly this system, including 3 of the semi-finalists! John Toshak is usually credited as the mastermind of the system, when the real visionary was Prof. de Leon back in 1976. Rinus Michels, the guru of total football, said that the idea came to him when watching rugby on TV. De Leon’s inspiration came from basketball. It worked, but Michels’s vision of football dominated the 70s and de Leon’s concept was neglected. Was it very far from total football? It depended on disciplined collective effort and not on individual brilliance. It required players to cover the whole field – just like total football does. Pleasant, not pleasant, the system not only survived, but trumped the original total football and is dominant in the early 21st century. It is a pity Prof. de Leon remains unrecognized, but at least in South America he is: credited for the development of football in Colombia and Venezuella among other things. Prophets are often disliked and diminished at home, so Defensor was heavily criticized, but champions they become under de Leon! Can’t take away that. Old horse like Cubilla fitted well in the system, something unusual for veterans with clout – they dislike, if capable at all of, changing their style. Perhaps the combination of de Leon and Cubilla was most important – the old player was aiming at coaching himself, and was eager and perceptive participant (in a few years time Cubilla became successful coach, leading the Paraguayan Olympia to winning Libertadores).

And that’s that about Uruguay in 1976 – ironically, a season considered bleak at the time was to stay as historic one. May be after the great play of Uruguay at the 2010 World Cup, the long gone season could be reviewed with more attention. As last, novelty, touch, Defensor have quite suitable name for defensive system of football.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

%5B1%5D.jpg)