USSR eventually won the bronze after winning 2-0 against the young and inexperienced Brazilian team. The victory pleased no one at home: it was not noted that there was no improvement even on Olympic level – once again just a third place. Tactics, form – everything was criticized. Terrible team.

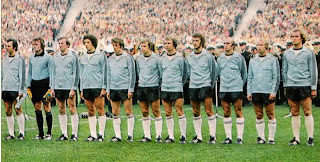

The ‘bronze’ team of 1976 Olympics: left to right: V. Kolotov-captain, V. Astapovsky, S. Reshko, A. Konkov, V. Veremeev, O. Blokhin, V. Matvienko, L. Buryak, V. Onishchenko, A. Minaev, V. Troshkin. According to Olympic rules, only those who actually played during the tournament received medals. V. Zvyagintzev, M. Fomenko, V. Fedorov, and L. Nazarenko got medals. Prokhorov and Kipiani did not. It was noted and mentioned in the Soviet press, as yet another bit of criticism: Lobanovsky did not have the decency to play David Kipiani just a few minutes, allowing the Georgian to get a medal. It was unfair. And truly was, but the outraged was only about Kipiani – Prokhorov was not mentioned at all. Apparently, it was fine for the reserve goalie not to play even a second.

The final was not great fun either – another tough, uninspired match, in which DDR overcome Poland 3-1.

Schade (14) scores the opening goal.

Montreal, 31st July, 1976

East Germany 3-1 (2-0) Poland

East Germany:

Croy, Lauck, Weise, Dörner, Kurbjuweit, Kische, Schade, Riediger (Bransch),Höfner, Lowe (Grobner), Hoffmann.

Poland:

Tomaszewski (Mowlik), Szymanowski, Wieczorek, Zmuda, Wawrowski, Maszczyk,Deyna, Kasperczak, Lato, Szarmach, Kmiecik.

Referee: Ramon Barreto (Uruguay)

Attendance: 71,617, Olympic Stadium

Scorers:

1-0 [ 7'] Schade; 2-0 [14'] Hoffmann; 2-1 [59'] Lato; 3-1 [79'] Höfner

There were no enthusiastic post-match commentaries and rightly so. It was observed that Poland struggled and decline seemingly settled. Deyna and Lato in particular were seemingly beyond their prime, but the rest of the team was apparently worse and not deserving even criticism. Well, Tomaszewsky, who was fantastic two years ago, had to be replaced at the final – a comment enough. Szarmach was the top scorer of the tournament with 6 goals – small consolation. Evidently, Poland was paying the heavy price for having small pool of good players: the heroes were getting old and new legs were unavailable.

DDR was organized, disciplined, and experienced – it was their regular national team and practically the same players who played at the 1974 World Cup. No surprises – it was dull, especially unattractive team, but in good condition and thorough. No stars, just regular team, dedicated to collective effort. It worked at the Olympics.

The Olympic champions plus two extra players (Kotte and Schnuphase): top, left to right: Walter (?) – assistant coach, Kische, Dorner, Riediger, Bransch, Grobner, Schade, Weber, Schnuphase, Georg Buschner – coach.

Middle: Kotte (?), Hoffmann, Croy, Grapentin, Lowe, Weise.

Bottom: Riedel, Hafner, Kurbjuweit, Lauck, Heider.

At the end of 1976 they were voted the team of the year in DDR, but outside home country the team attracted little interest. However, DDR was even better sample of the entirely collective football which was coming. No great individuals at all. And no fun, unfortunately.

Poland finished second – a team going downhill, it was judged.

Poland finished second – a team going downhill, it was judged.

The ‘bronze’ team of 1976 Olympics: left to right: V. Kolotov-captain, V. Astapovsky, S. Reshko, A. Konkov, V. Veremeev, O. Blokhin, V. Matvienko, L. Buryak, V. Onishchenko, A. Minaev, V. Troshkin. According to Olympic rules, only those who actually played during the tournament received medals. V. Zvyagintzev, M. Fomenko, V. Fedorov, and L. Nazarenko got medals. Prokhorov and Kipiani did not. It was noted and mentioned in the Soviet press, as yet another bit of criticism: Lobanovsky did not have the decency to play David Kipiani just a few minutes, allowing the Georgian to get a medal. It was unfair. And truly was, but the outraged was only about Kipiani – Prokhorov was not mentioned at all. Apparently, it was fine for the reserve goalie not to play even a second.

The final was not great fun either – another tough, uninspired match, in which DDR overcome Poland 3-1.

Schade (14) scores the opening goal.

Montreal, 31st July, 1976

East Germany 3-1 (2-0) Poland

East Germany:

Croy, Lauck, Weise, Dörner, Kurbjuweit, Kische, Schade, Riediger (Bransch),Höfner, Lowe (Grobner), Hoffmann.

Poland:

Tomaszewski (Mowlik), Szymanowski, Wieczorek, Zmuda, Wawrowski, Maszczyk,Deyna, Kasperczak, Lato, Szarmach, Kmiecik.

Referee: Ramon Barreto (Uruguay)

Attendance: 71,617, Olympic Stadium

Scorers:

1-0 [ 7'] Schade; 2-0 [14'] Hoffmann; 2-1 [59'] Lato; 3-1 [79'] Höfner

There were no enthusiastic post-match commentaries and rightly so. It was observed that Poland struggled and decline seemingly settled. Deyna and Lato in particular were seemingly beyond their prime, but the rest of the team was apparently worse and not deserving even criticism. Well, Tomaszewsky, who was fantastic two years ago, had to be replaced at the final – a comment enough. Szarmach was the top scorer of the tournament with 6 goals – small consolation. Evidently, Poland was paying the heavy price for having small pool of good players: the heroes were getting old and new legs were unavailable.

DDR was organized, disciplined, and experienced – it was their regular national team and practically the same players who played at the 1974 World Cup. No surprises – it was dull, especially unattractive team, but in good condition and thorough. No stars, just regular team, dedicated to collective effort. It worked at the Olympics.

The Olympic champions plus two extra players (Kotte and Schnuphase): top, left to right: Walter (?) – assistant coach, Kische, Dorner, Riediger, Bransch, Grobner, Schade, Weber, Schnuphase, Georg Buschner – coach.

Middle: Kotte (?), Hoffmann, Croy, Grapentin, Lowe, Weise.

Bottom: Riedel, Hafner, Kurbjuweit, Lauck, Heider.

At the end of 1976 they were voted the team of the year in DDR, but outside home country the team attracted little interest. However, DDR was even better sample of the entirely collective football which was coming. No great individuals at all. And no fun, unfortunately.

Poland finished second – a team going downhill, it was judged.

Poland finished second – a team going downhill, it was judged.

Fighting the mud along with DDR to another tie. Weisse strikes somehow, Gogh is too late to prevent.

Fighting the mud along with DDR to another tie. Weisse strikes somehow, Gogh is too late to prevent.

Svehlik escapes from Angelini’s tackle.

Svehlik escapes from Angelini’s tackle.