Alexander Kostov, or simply Sasho, ended his career in 1971. Born in 1938, he played for Levsky (Sofia) from 1955 to 1971, except in the 1960-61 season, when he was called for military service and played for Botev (Plovdiv) as most Levsky’s players of his generation did when soldiering. Sasho played 301 games and scored 78 goals (20 games and 13 goals for Botev; the rest for Levsky). He also played 7 games for the national team and scored 1 goal.

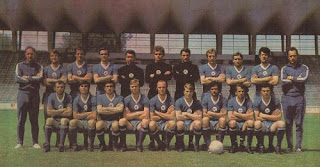

The last greeting to the public.

It is not his goals and trademark moves of the left winger which made him one of the most loved and long remembered players of Levsky, however. Sasho is a legend because of his pranks and jokes – his ability to entertain the fans. For this ability fans forgave him anything and coaches put up with him. A brief selection:

The goalkeeper missed the cross and Sasho got the ball in front of wide open net. The goalie did not bother the get up; both teams started walking to the centre – it was absolutely obvious goal. But Sasho stopped the ball in front of the goal line and addressed the goalie in words and obvious to the crowd gestures: ‘come on, get up, don’t lay in the dust. Stand up, like a man’. The goalie could not believe and did not move at first, so Sasho encouraged him a little more, until the keeper get up and actually rushed for the ball. Only then Sasho gently kicked it in the net, just enough to cross the goal line.

Levsky was playing against Lokomotiv (Sofia) and Kotkov (still a Lokomotiv player) was preparing for a corner kick against Levsky. ‘Kitten, pass me the ball, please’, said Sasho, who was supposed to be defending. ‘I’ll pass it back to you.’ ‘You are going to make fool of me’, answered suspicious Kotkov, who knew Sasho well enough to trust him. ‘I promise you!’, said Sasho sweetly. Kotkov risked it and pass the ball to… an opposition player. Sasho elegantly passed the ball back with a header. On both accasions Sasho was suspended by the Federation for ‘putting the game in disrepute’ and ‘making mockery of the fans’. But the fans even of opposite teams did not feel offended – they loved the pranks and laughed heartily.

It is not his goals and trademark moves of the left winger which made him one of the most loved and long remembered players of Levsky, however. Sasho is a legend because of his pranks and jokes – his ability to entertain the fans. For this ability fans forgave him anything and coaches put up with him. A brief selection:

The goalkeeper missed the cross and Sasho got the ball in front of wide open net. The goalie did not bother the get up; both teams started walking to the centre – it was absolutely obvious goal. But Sasho stopped the ball in front of the goal line and addressed the goalie in words and obvious to the crowd gestures: ‘come on, get up, don’t lay in the dust. Stand up, like a man’. The goalie could not believe and did not move at first, so Sasho encouraged him a little more, until the keeper get up and actually rushed for the ball. Only then Sasho gently kicked it in the net, just enough to cross the goal line.

Levsky was playing against Lokomotiv (Sofia) and Kotkov (still a Lokomotiv player) was preparing for a corner kick against Levsky. ‘Kitten, pass me the ball, please’, said Sasho, who was supposed to be defending. ‘I’ll pass it back to you.’ ‘You are going to make fool of me’, answered suspicious Kotkov, who knew Sasho well enough to trust him. ‘I promise you!’, said Sasho sweetly. Kotkov risked it and pass the ball to… an opposition player. Sasho elegantly passed the ball back with a header. On both accasions Sasho was suspended by the Federation for ‘putting the game in disrepute’ and ‘making mockery of the fans’. But the fans even of opposite teams did not feel offended – they loved the pranks and laughed heartily.

Sasho was dangerous left wing and often the other team’s coach dispatched a defender to keep an eye on Kostov through the game personally, doing nothing else. Once a young player was to do this and Sasho felt the guy was too zealous… so when a pass came to him, he just stopped the ball, leaving it motionless a bit away from himself. Sasho stayed motionless too, and so was the defender watching him tensely. Suddenly Sasho dashed ahead and the defender followed him. But the ball remained where it was, Sasho run without it. Then he returned back and did the same one more time, and the defender again run after him and not for the ball. Sasho came back, kicked the ball a little more away from himself and started looking around seemingly absent minded. The defender finally mastered some courage and run for the ball – and in the very last moment Sasho reached for it, tricked the defender and attacked when the defender, kept by his own momentum was still running in the opposite direction.

Two verbal jokes from the legendary 7-2 win against the archenemy CSKA are still well remembered. During the match Sasho approached CSKA’s right winger Tzvetan Atanasov: ‘Tzetzo, they tell me you are the fastest player in CSKA. Is this right?’ ‘Yes’, answered Atanasov, ‘I am.’ ‘Good’, said Sasho innocently. ‘Why don’t you dash to your stadium (CSKA’s stadium is practically next to the National stadium where the derby was played) and bring the score board from there. See, there is no more space on this one for names of goal scorers.’ After the game Sasho commented the fact that CSKA scored the first and last goal in the game: ‘Oh, we let them score first to see how many fans they have. We let them score the last goal to see how many remained.’ At least Levsky’s fans saw double-edged joke: it sounded just innocent comment on the fate of CSKA’s fans in this game, but it also was interpreted to be a comment on the artificial nature of CSKA – a ‘new’ and Communist founded club, they had to built support by hook and crook in the early years – it was a common practice in the early years (and kept later as well) to bring soldiers to CSKA matches. Their officers commanded the soldiers to cheer CSKA, thus presenting ‘fans’ and large crowds. It was felt that CSKA’s fans were somewhat artificial, not real fans, and if the club is not strong, they will move to other clubs.

But it was not only pranks, and jokes entertaining the fans – Sasho did not spare teammates and coaches. Once he emerged for a training session with cigarette in his mouth. Rudolf Vitlacil, the strict disciplinarian Czechoslovakian coach of Levsky and the national team, was ready to explode. But when Sasho came near and Vitlacil was just opening his mouth to shout and punish, the player took the cigarette out from his mouth, unwrapped it, and casually put it back, starting munching. It was a bubble gum, shaped as cigarette.

But it was not only pranks, and jokes entertaining the fans – Sasho did not spare teammates and coaches. Once he emerged for a training session with cigarette in his mouth. Rudolf Vitlacil, the strict disciplinarian Czechoslovakian coach of Levsky and the national team, was ready to explode. But when Sasho came near and Vitlacil was just opening his mouth to shout and punish, the player took the cigarette out from his mouth, unwrapped it, and casually put it back, starting munching. It was a bubble gum, shaped as cigarette.

During the qualification match for the World Cup against Israel, Sasho saw Vitlacil getting a reserve player to warm up. Substitute was coming. ‘Gundy’, casually said Sasho to Asparukhov, ‘Vitlacil is replacing you. He just told me to tell you.’ Asparukhov was disciplined player and took the news to be true. When substitute was signaled, he went to get replaced. ‘Where are you going?’, asked him puzzled Vitlacil. ‘Well, Sasho told me I am to be replaced.’ ‘Who, the hell, is Sasho to tell you what to do?’, exploded the coach, who had in mind entirely different player to be substituted. No wonder Sasho played only times for the national team. But normally a coach had to face destruction of his tactics in very different way: Sasho was not exactly a workaholic, and did not bother to play much against obviously weaker teams. It was a staple – since the roof of Levsky’s stadium shades only half of the pitch, Sasho simply stayed in the cooler shadowy half. When teams changed sides for the second half, Sasho did not go to the sunny part of the pitch, but remained in the shadowy part, thus doubling the right winger. And becoming an extra player on this flank, he did nothing at all – just walked around, cracking jokes with teammates, the opposite team, the referees, and sometime with the fans. There was nothing on earth to move him under the merciless rays of sunshine. The fans normally do not tolerate laziness, but Sasho they did and enjoyed – it was something eagerly waited to happen, and there were bets – was Sasho, by mere mistake, to expose himself to sunshine and break accidental sweat or not? The player never disappointed – from time to time he was coming dangerously close to the sunny place, it looked like he was going to enter sunny zone… but he never did. He was teasing the fans. Yes, tactics went to dust… but the public loved the pranks. When Sasho retired, a big part of old football disappeared – Sasho was fun. He constantly reminded everybody that football is not something severely serious and businesslike – it was a game after all. Something to be enjoyed. Sasho brought laughter to the stadium. For all his pranks, even his victims from other clubs did not hate him. Occasionally, like Kotkov, some players joined his prank to the delight of the fans of both teams. Football is fun. I miss the fun – it was gone when players like Sasho retired. In a way, 1971 marks the end of entertaining football. After this year it was steadily becoming more and more ‘serious’ affair, a business. No laughter… the end of laughter. Sadly, fun was gone.