Final. Bets on West Germany, partly because they played well against Yugoslavia, partly because it was difficult to discard Beckenbauer, partly because Czechoslovakia’s ‘luck’ was bound to end. One thing was strange, though: the finals attracted smaller crowds than the semi-finals. Yugoslavia’s elimination was the main reason, but still it was strange: Holland – Czechoslovakia was attended by more fans than the final deciding who will be the European champion. 70 000 went to Crvena zvezda stadium to watch Yugoslavia – West Germany; less than half the number went back to the same stadium to see the final. In a way, the victory of the Germans was in the bag and it was not even interesting to witness… CSSR had only one change from the previous match – Svehlik instead the suspended Pollak. The Germans were pretty much the same too – Dieter Muller was a starter this time, taking the place of disappointing Danner. The match started and the goals quickly followed – but they were not in the Czechoslovakian net. By the 25th minute it was 2-0 for CSSR! It was a mirror image of the semi-final against Yugoslavia – the Germans suffered heavy assaults, resulting in 2 early goals.

Svehlik scoring the first goal of the final in the 8th minute.

Full backs defend, right? It all depends – Vogts tries to defend, but Karol Dobias – 2-0 in the 25th minute.

This time the Germans responded much quicker than they did against Yugoslavia: they scored in the 28th minute. And it was Dieter Muller again – the magic name continued to work, West Germany truly found her new Muller. Or so appeared. The first half ended 2-1. It was entertaining, fast 45 minutes of attacking football, both sides quite equally dangerous and the Czechoslovakians missing golden opportunity for a third goal.

The second goal was mostly German – they attacked constantly, pressing the Czechoslovakians in defense. Ivo Viktor had to work hard, but he managed.

Fogts, Moder, Beckenbauer and the ball…

Both teams fought well, CSSR’s defense surviving constant attacks and it looked like no fresh goals were to materialize. The public started leaving the stadium – there was a minute left, the match was practically over, but there was a good reason to stay to the final whistle when Germans were playing… Holzenbein scored with a header precisely in the 89th minute. Remember Bayern – Atletico Madrid from the spring of 1974? Regular time ended 2-2, thus, every match of the finals went into extra time! Extraordinary!

Overtime, however, was lesser fun – both teams looked tired and cautious. Changes were made early – once again Flohe came on the pitch at the beginning of the second half (replacing Wimmer). Then Bongartz replaced Beer in the 80th minute – Schon tried to put some vim into his team, when Czechoslovakia waited and used clearly defensive tactic – another defender, Jurkemik, replaced Svehlik in the 79th minute. There was no room for fresh legs during the extra time, except for CSSR – and this time they decided on striker: Vesely replaced Dobias in the 94th minute. Nothing happened, though – overtime ended and penalty shoot-out was to decide the European Championship. Always a gamble. Still, West Germany had better odds – better goalkeeper; better shooters; iron nerves. Fate was playing a joke of repetitions this year… the third one was during the penalties. They went one for one, nobody missing, until Uli Hoeness took the forth for the Germans and… shoot the ball over the crossbar. Remember him missing a penalty in the 1974 World Cup match against Poland? Now again. Since Czechoslovakia had the first penalty, their last had the chance to decide the championship. Antonin Panenka kick the ball and it was 5-3! The Germans lost. It was a penalty to be discussed for years – until now. The ‘cheeky’ penalty, the risk Panenka took… he was and is criticized for his ‘casual’ approach, seen as carelessness by some. Yet, it was the winning goal.

Light ball right in the middle of Maier’s net. If the goalie did not move, the ball was to bounce off him and away… but goalkeepers always plunge aside. Was it undue risk? Was it a cool calculation? Panenka leans to the former in his interviews. Well, it is easy to speak after the fact.

So why the fuss over Panenka’s penalty? Well, it looks like the same as the one Jurkemik delivered a bit earlier. Except Jurkemik really kicked the ball, and Panenka did not.

Never mind, though: thanks to Panenka CSSR won!

The happy goalscorer runs euphoric.

And Czechoslvakia, already dressed in Germans shirts, lifted the European cup. Happy winners of the 5th European championship – nobody managed to win the tournament twice so far! New European champions again!

Beograd, June 20, Crvena zvezda

Czechoslovakia 2-2 West Germany [aet]

[Svehlík 8, Dobiás 25; D.Müller 28, Hölzenbein 89]

[ref: Gonella (Italy); att: 35,000]

Czechoslovakia win 5-3 on penalties

[Masny 1-0, Bonhof 1-1; Nehoda 2-1, Flohe 2-2; Ondrus 3-2, Bongarts 3-3;

Jurkemik 4-3, U.Hoeneß 4-3 (over the crossbar); Panenka 5-3]

Czechoslovakia: Viktor, Pivarník, Ondrus, Capkovic, Gögh, Dobiás (94 Vesely),Móder, Panenka, Masny, Svehlík (79 Jurkemik), Nehoda

West Germany: Maier, Vogts, Schwarzenbeck, Beckenbauer, Dietz, Wimmer (46 Flohe), Bonhof, Beer (80 Bongartz), U.Hoeneß, D.Müller, Hölzenbein

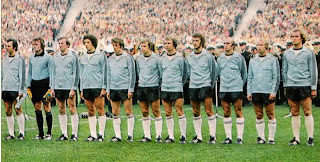

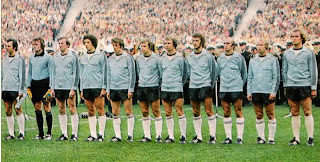

German losers… what else, since second place was actually a major step down for the reigning world champions. From left: Beckenbauer, Maier, Schwarzenbeck, D. Muller, Wimmer, Dietz, Holzenbein, Bonhof, Beer, Vogts, Hoeness.

Brand new European Champions! Top, left to right: Vaclav Jezek – coach, Ladislav Jurkemik, Anton Ondrus, Dusan Galis, Alexander Vencel, Antonin Panenka, Ivo Viktor, Jozef Capkovic, Marian Masny, Pavol Biros, Zdenek Nehoda, Jozef Venglos – assistant coach.

Bottom: Miloslav Kundrat – team’s doctor, Ladislav Petras, Karol Dobias, Jan Pivarnik, Lubomir Knapp, Jan Svehlik, Koloman Gogh, Jaroslav Pollak, Jozef Moder, Vlastimil Ruzicka – masseur.

Oh, well – almost the team: L. Knapp did not make the final selection, but Jozef Barmos, Dusan Herda, Frantisek Vesely, Frantisek Stambachr, and Premysl Bicovsky did. From them only Vesely played at the finals. He was 33 years old at the time – and still enough playing years ahead of him, as it turned out.

Poland finished second – a team going downhill, it was judged.

Poland finished second – a team going downhill, it was judged.

Fighting the mud along with DDR to another tie. Weisse strikes somehow, Gogh is too late to prevent.

Fighting the mud along with DDR to another tie. Weisse strikes somehow, Gogh is too late to prevent.

Svehlik escapes from Angelini’s tackle.

Svehlik escapes from Angelini’s tackle.